Halloween and Momijigari ∣ October in Japan’s Events

Photo:©Fukushima Prefecture Tourism and Products Association

The sky is clear, the mountains begin to turn red, and October marks the seasonal transition from summer to winter. Through events like koromogae (clothing changeover) and autumn festivals, people’s lives naturally align with the rhythm of nature.

Modern Events Expanding in Autumn

Halloween (Shibuya, Theme Parks, Official City Events)

October 31 is now one of Japan’s signature modern events. In the past, “Shibuya Halloween,” where young people gathered in the streets wearing costumes, became a social phenomenon. However, in recent years, street gatherings and costumes in Shibuya have been prohibited for safety reasons, and the trend has shifted toward municipalities and commercial facilities holding official events.

At present, people enjoy Halloween at the Ikebukuro Halloween Cosplay Festival, where cosplayers gather in large numbers, or at theme parks such as Tokyo Disneyland and Sanrio Puroland, as well as at city-wide official events in Kamiyacho and Futakotamagawa. This reflects how Halloween in Japan has become established as a unique culture centered on organized and secure venues.

For children, it is often celebrated by dressing up with friends or at local community events. However, unlike overseas, it does not involve going around to the houses of strangers to receive sweets. In Japan, Halloween has rather become an event characterized more as an “adult festival.”

※Information current as of September 2025.

Japanese School Festivals and Sports Days

Autumn is also the high season for school events. School festivals are opportunities where students display their creativity and learning through performances, exhibitions, and food stalls, and they are occasions that local residents and parents also enjoy.

Sports days (undokai) show a recent division into two different trends. Traditionally, they were most often held in October to take advantage of the pleasant climate, but due to exam schedules and the structure of the school curriculum, more and more schools now hold them in May. Autumn sports days remain as festive, community-involving events, while spring sports days are appreciated for avoiding heat and fitting better with the academic schedule.

Reading Week in Japan (October 27 – November 9)

Reading Week is a nationwide campaign that coincides with Culture Day and promotes reading through events held in schools, libraries, and bookstores. Although it may appear to be a modest event, it is actually an important season for the publishing world and bookstores.

Past Reading Week posters

In Japan, books are sold under the resale price maintenance system, meaning that the price of books is the same everywhere, from big cities to rural towns. Because of this, there is no price competition through discounting. Instead, bookstores create fairs and themed promotions, while e-books, such as Amazon Kindle, provide point-back or cashback-style campaigns. Thus, Reading Week becomes a subtle yet significant period of activity for book lovers.

Traditional Events Marking the Seasonal Transition

Momijigari: Autumn Leaves Viewing in Japan

This is a long-standing tradition that began among the aristocrats of the Heian period. As mountains and gardens blaze in brilliant colors of red and yellow, it attracts travelers from all over. It remains one of the defining activities of autumn in Japan. Famous locations include Arashiyama and Toganoo in Kyoto, as well as Irohazaka in Nikko, which draw visitors from around the world.

Koromogae (Seasonal Clothing Change, October 1)

On October 1, there is a nationwide changeover from summer clothing to winter clothing. School and workplace uniforms are all switched on the same day, and this shared timing embodies the Japanese sense of seasonal rhythm in daily life.

Jūsanya (The “Chestnut Moon” or “Bean Moon”)

This is the moon-viewing occasion that follows the more famous Fifteenth Night (Jūgoya). People offer chestnuts and beans, which is why it is also called the “Chestnut Moon” or “Bean Moon.” Traditionally, it was considered unlucky to celebrate only one of the two, so both were observed together for good fortune. In the present day, however, the Fifteenth Night is much more prominent, and Jūsanya is less widely practiced, though some regions still preserve it.

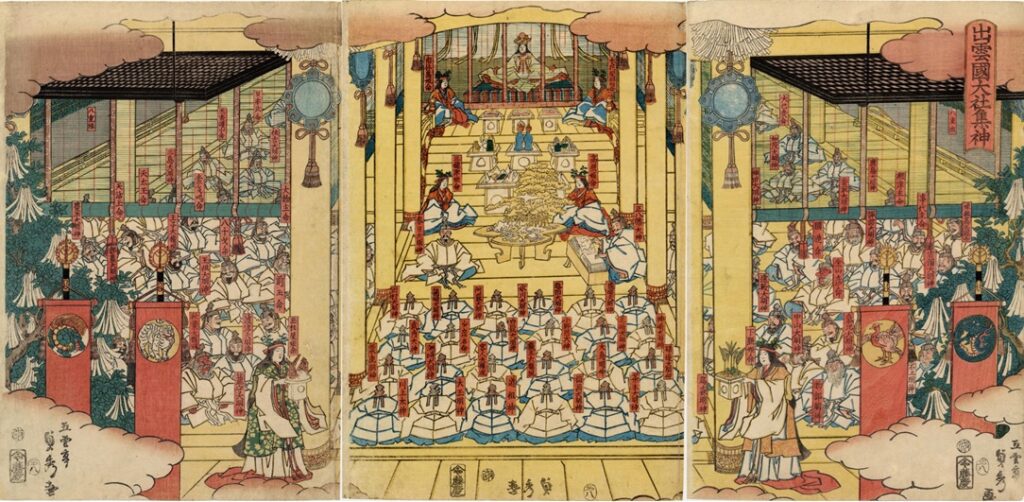

Kannazuki and Kamiarizuki

In the old lunar calendar, October was called Kannazuki, meaning “the month without gods.” This name comes from the belief that the deities from all over Japan leave their shrines to gather at Izumo Taisha, where they hold a great meeting. For this reason, in all other regions the gods are considered absent. In Izumo, however, it is the opposite, and October is called Kamiarizuki, “the month with gods,” since the deities are welcomed there.

This custom reflects the Shinto worldview of yaoyorozu no kami (“eight million gods”), which sees the divine not as a single absolute being but as a vast community of deities who cooperate and deliberate together. For those from monotheistic cultural backgrounds, the idea of gods leaving their places to hold a meeting may seem strange, but it clearly expresses how in Japan gods are thought of as multiple and communal rather than singular and absolute.

Grand Autumn Festivals Across Japan

October is the harvest season, and all over the country people hold autumn festivals to give thanks for an abundant crop and to honor the gods.

- Nada Kenka Matsuri (Himeji, Hyogo): A heroic festival in which three portable shrines are violently crashed against each other, known nationwide for its bravery.

- Nagasaki Kunchi (Suwa Shrine, Nagasaki): The largest festival in Nagasaki, featuring dragon dances and ornate kazari-boko floats, with over 300 years of history.

- Jidai Matsuri (Kyoto): A historical parade where participants march in costumes from the Heian through the Meiji periods, reenacting Kyoto’s long history. Counted as one of Kyoto’s three great festivals, along with the Aoi Matsuri and Gion Matsuri.

- Kannamesai (Ise Grand Shrine): The most important Shinto ritual of Ise Jingu, where the first rice harvest of the year is dedicated to the deities.

Editor and writer from Japan. Not the best at English, but I share real stories with heart and honesty — aiming to connect cultures and ideas that matter.