Why Japanese Manga Captivates Adults Around the World

In many parts of the world, the idea that “comics are for kids” is still taken for granted.

In places like the U.S. and Europe, comics are often viewed as something childish, something people are expected to grow out of.

Yet Japanese manga and anime have gone global—not just among kids, but among adults.

So why is it that Japanese works alone seem to transcend age and resonate across generations?

I believe the answer lies in Japan’s unique cultural and social background. Join me in thinking about what pocket money, screen quotas, and youth culture might have to do with the way Japanese manga connects with adults.

- Pocket money culture

- Screen quota systems

- Juvenile literary tradition

A Market Where Children Had Purchasing Power

In Japan, it’s long been customary to give children pocket money—allowances, New Year’s cash gifts, and so on.

This tradition, said to date back to the Edo period, gave kids freedom to spend money however they wanted, with minimal interference from adults.

In part, this tradition also served as a way to teach children basic financial literacy—how to manage limited money, weigh priorities, and make decisions on their own.

And what that created was something truly unique: a functioning, child-driven market.

I remember getting ¥1,000 a month as pocket money when I was a kid. I wanted everything—after-school snacks, sparkly stickers, manga—but I couldn’t afford it all. So instead of buying manga magazines every month, I’d read them at my friends’ houses and save my money to buy only the volumes of the series I truly loved.

And the key point? Nobody stopped us.

There was no adult disapproval, no “comics are a waste of money” attitude.

Children were recognized as valid consumers, and the publishing industry catered directly to them.

In other words, Japan had a cultural ecosystem that allowed children not only to read manga, but to choose and buy them for themselves—a small-scale market powered entirely by kids.

How Japanese Animation Survived and Spread Globally

Another key to the global success of Japanese anime lies in something seemingly unrelated: screen quota systems.

Many countries introduced screen quotas as a way to protect local media industries from being dominated by Hollywood.

These policies required a certain percentage of broadcast content to be domestically produced.

Thanks to these quotas, Japanese films and anime were not pushed out by Hollywood content and maintained steady airtime on domestic screens.

Without these protections, classics like Galaxy Express 999 or Future Boy Conan may have faded into obscurity.

But here’s the twist: in countries where local children’s programming was scarce, Japanese anime was often re-edited and aired as if it were local content.

For example:

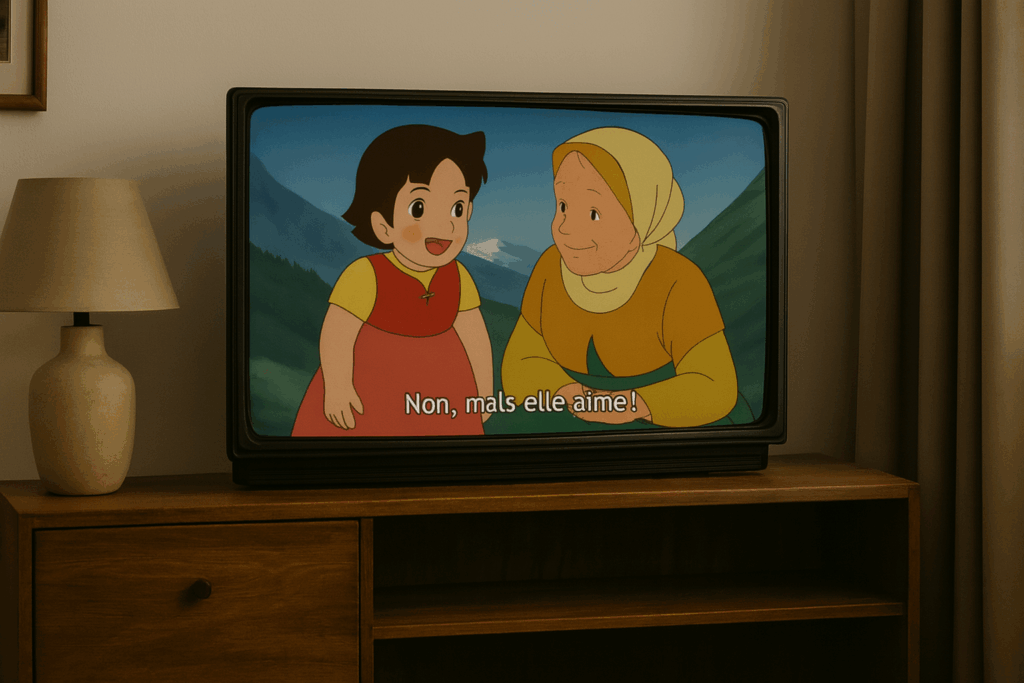

- Some Swiss viewers believed Heidi, Girl of the Alps was a Swiss production.

- In Finland, many grew up watching Moomin without realizing it was animated by Tezuka Productions in Japan.

- In some regions, fight scenes were completely cut, replaced with voiceovers from local adults explaining the action—urban legend or not, it happened.

Thus, Japanese anime quietly took root in foreign lands.

And even today, countries like South Korea, France, and Canada continue to use screen quotas to protect and promote local culture.

A Tradition of Storytelling That Carries Questions Across Generations

But what truly makes Japanese manga unique is this: they’re not just fun—they’re thoughtful.

From the very beginning, Japanese creators didn’t treat manga as throwaway entertainment.

Pioneers like Osamu Tezuka embedded their stories with deep philosophical and social themes, masked in accessible storytelling.

Tezuka’s Buddha dives into religious ethics and human suffering.

Phoenix tackles life, death, and reincarnation.

Even Doraemon, which may look like a lighthearted sci-fi comedy, asks: What kind of future are we building? What happens when we rely too much on technology?

In Japan, creators didn’t dumb things down for kids.

Instead, they trusted young readers to grapple with big questions, and those readers, growing up, often became creators themselves—passing down new questions to the next generation.

This cycle gave rise to what can be called a “juvenile literary tradition”, where manga functioned not only as entertainment, but as a tool for critical thinking.

And the tradition lives on.

Take Chi: Chikyū no Undō ni Tsuite (Chi: On the Movements of the Earth), a story about the dangers and hope of seeking knowledge.

Or Naruto, which explores themes like friendship, effort, and self-worth in a way that resonates even more deeply with adults.

Japanese manga are not just page-turners.

They’re vessels for introspection, values, and the kind of philosophical reflection that stays with you long after you finish reading.

Comics That Look Like They’re for Kids, but Speak to Adults

As we’ve seen, Japanese manga didn’t become a global phenomenon by accident.

- Pocket money gave children the agency to buy what they wanted.

- Screen quotas preserved Japanese anime and helped sneak it into global markets.

- A tradition of embedding messages and moral complexity kept manga alive—not just as content, but as culture.

That’s why Japanese manga offers depth and meaning that speak to adults, not just kids.

To anyone who still believes “comics are just for children”—

try opening a volume of Japanese manga.

It might look like just a story, but sometimes it turns out to be a question—one that quietly follows us into adulthood.

You might also be interested in these articles

■Japan’s 800-Year Obsession with Turning Everything into Characters

Editor and writer from Japan. Not the best at English, but I share real stories with heart and honesty — aiming to connect cultures and ideas that matter.