Sumo Was Once a Sacred Ritual, Long Before It Became a Sport

Sumo is not merely a form of combat sport.

It began as a sacred ritual dedicated to the gods, evolved into training for samurai, and later became a popular form of entertainment among the people.

Every gesture made by a sumo wrestler carries meaning that transcends victory or defeat.

Throwing salt, stamping the ground (shiko), exchanging bows—each movement is a prayer that has been passed down for over a thousand years.

Origins of Sumo — From Myth to Ritual

The origins of sumo can be traced back to the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters), where the gods Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata wrestled for control over the land.

In the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan), it is said that Nomi no Sukune and Taima no Kehaya competed before Emperor Suinin, marking what is considered the first “imperial viewing” of sumo.

During the Nara and Heian periods, the Sumai no Sechie—an annual court ceremony featuring sumo matches before the emperor—became an official state event.

Warriors and Power — Sumo as Martial Training

In the Kamakura period, shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo hosted Jōran-zumō (sumo viewed by a lord) at Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine, promoting sumo as a form of warrior training.

During the Sengoku period, Oda Nobunaga organized matches at Jōrakuji Temple and rewarded the victors.

At that time, there was no ring (dohyō) yet, and bouts resembled grappling, but the spirit of courtesy was already deeply rooted.

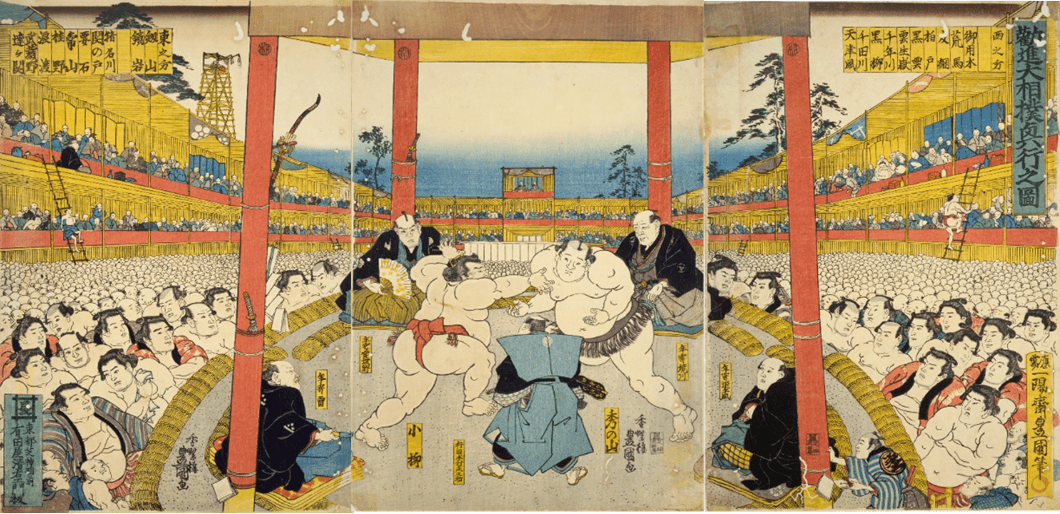

Edo Period — From Ritual to Entertainment

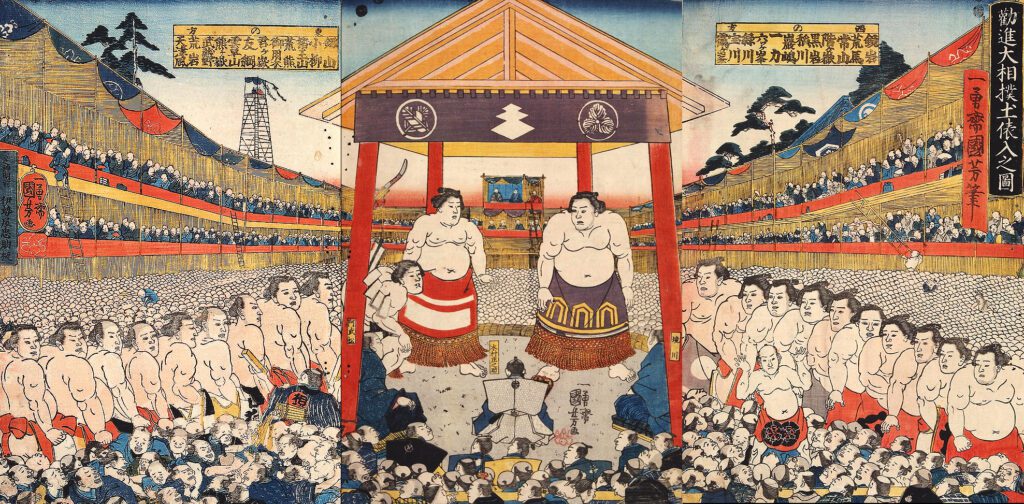

In the Edo period, sumo spread across Japan as a dedication ceremony at shrines.

This gave rise to kanjin-zumō—public matches held to raise funds for temple or shrine repairs.

Temporary dohyō were set up along the Sumida River, surrounded by food stalls and cheering crowds.

It was during this era that the banzuke (official ranking list) and the ceremonial dohyō-iri (ring-entering ritual) were established, and wrestlers became popular subjects in ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

Sumo transformed from “a ritual for the gods” into “a passion of the people.”

From National Sport to Global Stage

In the Meiji era, the tenran-zumō (sumo before the emperor) was revived, solidifying sumo’s position as a national symbol.

By the Shōwa era, the Ryōgoku Kokugikan arena was built, the Sumo Association was formed, and television broadcasts spread the sport nationwide.

After World War II, sumo became officially recognized as Japan’s kokugi—the national sport—and has since gained fans in more than 70 countries.

Today, wrestlers from Mongolia and Georgia rise to the top ranks, and international tournaments draw full audiences around the world.

The Hierarchy — Ranks, Salaries, and Sponsorships

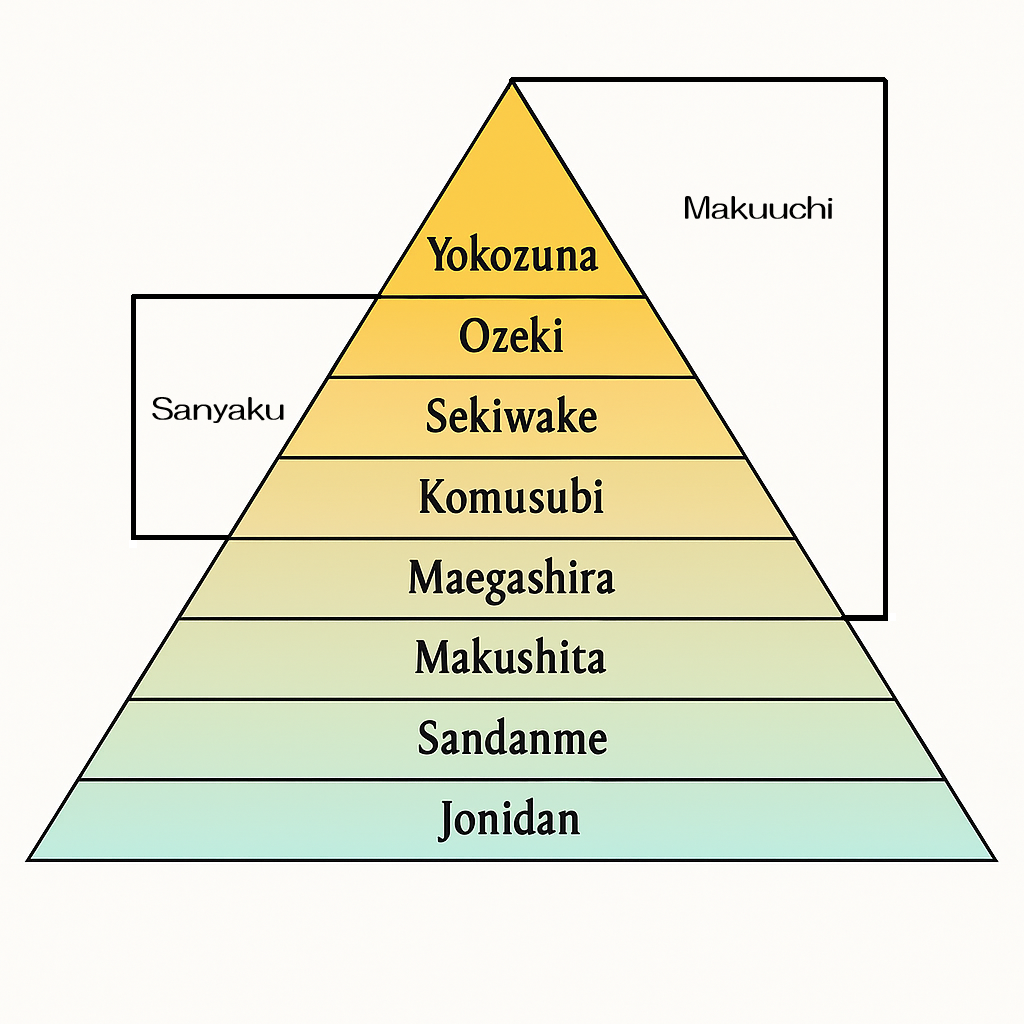

The world of sumo is defined by strict hierarchy.

At the top stands the Yokozuna, followed by Ōzeki, Sekiwake, Komusubi, Maegashira, Jūryō, and the lower divisions.

Promotion to Yokozuna requires two consecutive championships as an Ōzeki or equivalent performance, along with recommendation by the council.

A Yokozuna is expected not only to be the strongest, but also to embody dignity and exemplary conduct.

Monthly salaries depend on rank—approximately ¥3,000,000 for a Yokozuna, ¥2,500,000 for an Ōzeki, and ¥1,100,000 for a Jūryō wrestler.

Prize money, sponsorship rewards, and kenshō-kin (sponsored envelopes presented before matches) supplement their income.

The banners displaying company logos around the ring are a hallmark of sumo’s unique sponsorship culture.

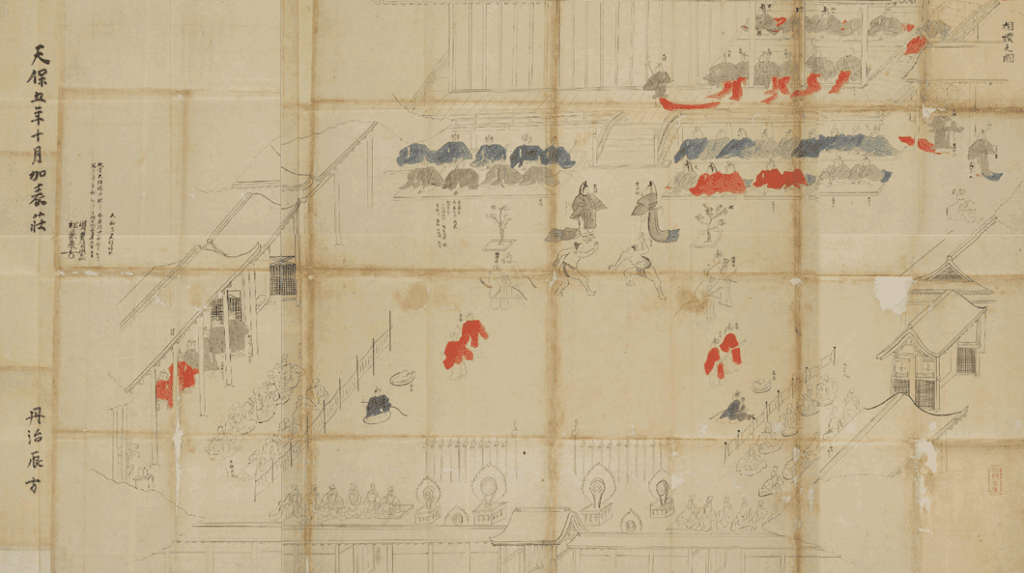

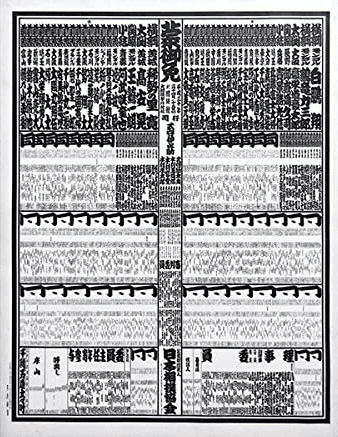

The Banzuke — A Sacred Ranking Sheet

The banzuke is an official document listing the ranks of wrestlers, referees, and attendants—a formal record of the sumo world.

It is handwritten by a motogaki (chief referee) in the distinctive sumo script, with thicker and larger characters for higher ranks.

At the center appears the phrase “Mō go men” (literally, “with imperial permission”), along with the tournament date and location.

For fans, the banzuke serves as both a historical record and a collectible artwork—often framed as a souvenir, especially among overseas enthusiasts.

The Season and How to Watch Sumo

Professional tournaments (honbasho) are held six times a year across Japan:

January, May, and September in Tokyo (Ryōgoku Kokugikan), March in Osaka, July in Nagoya, and November in Fukuoka.

Each tournament lasts 15 days, with wrestlers competing once per day.

Tickets can be purchased online or at convenience stores, though masu-seki (box seats) sell out quickly and should be reserved in advance.

During matches, it is customary to remain seated and observe quietly when wrestlers enter the ring.

Throwing salt is a purification ritual, not a performance, and throwing cushions after a bout—though once traditional—is now prohibited for safety reasons.

The Spirit of the Dohyō

Each wrestler lives and trains within a heya (sumo stable), where they learn both technique and etiquette from their master.

A heya is not merely a training place, but a communal household preserving lineage and discipline.

The circular dohyō, 4.55 meters in diameter, represents the cosmos itself.

Four colored tassels hang above to symbolize the cardinal directions, while the yobidashi (ring attendants) shape the clay with great care.

From the throwing of salt, the stomping of shiko, the crouching stance (sonkyo), to the hand gestures before a bout (tegatana), each movement preserves the prayers of centuries past.

Beyond Victory — The Spirit That Endures

Sumo is both a sport of strength and a way of approaching the divine.

Behind every match lies the Japanese belief that “courtesy begins and ends all things.”

In its silence and tension, the spirit of Japan—refined over more than a thousand years—continues to live on.

And today, the spirit of the dohyō continues to inspire people far beyond Japan’s shores.

Editor and writer from Japan. Not the best at English, but I share real stories with heart and honesty — aiming to connect cultures and ideas that matter.