Gyotaku ∣ Japan’s Fish Printing Culture from the Edo Period to the Present

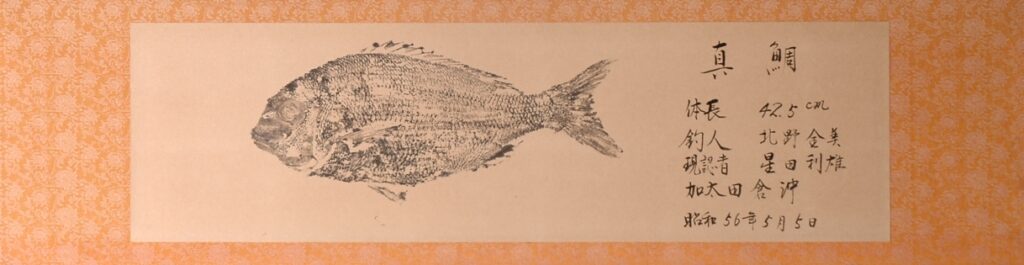

Gyotaku (魚拓) is a uniquely Japanese method in which anglers transfer the form of a fish onto paper or cloth, preserving it as a record. The accidental blurring of ink and the bold composition can appear fresh and striking even to those who have never fished. While serving as proof of a catch for fishing enthusiasts, in recent years gyotaku has also attracted attention from people interested in art.

Edo Samurai and the Origins of Gyotaku

The oldest surviving gyotaku in Japan is “The Crucian Carp of Kinshi-bori,” created in February 1839 (Tenpō 10), when Sakai Tadayoshi, the lord of the Shōnai domain, caught a crucian carp in Kinshi-bori in Edo. This piece is now preserved at the Tsuruoka City Local History Museum.

During the later Edo period, Japan experienced long years of peace without war. Samurai lost opportunities to draw their swords, and some sought new ways to train both body and mind. Within the Shōnai domain, sea fishing was encouraged as a form of discipline. Facing nature was thought to foster concentration and patience, which could serve as practice in place of battle. Large fish that were caught were sometimes compared to “the head of a defeated enemy general,” and it is said that they were taken as gyotaku and presented to the domain lord. In this way, gyotaku spread as a visible result of spiritual training.

Techniques of Gyotaku: Direct and Indirect Methods

There are two main techniques of gyotaku.

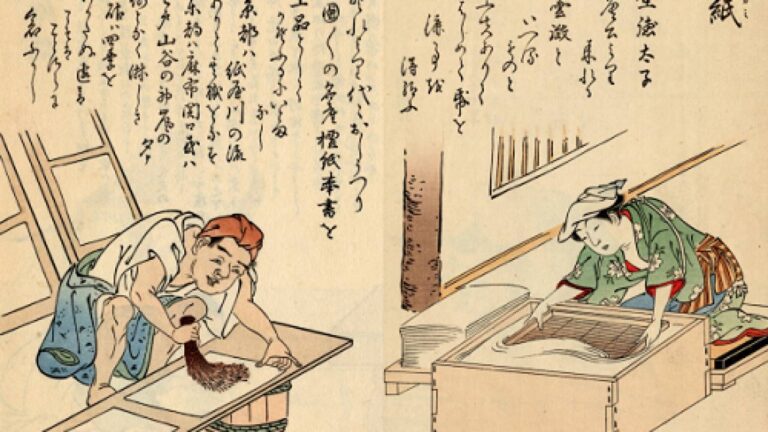

The direct method begins by washing the fish to remove slime and dirt, then carefully wiping away moisture. Ink is applied directly onto the body surface, and Japanese paper is pressed against it to take the impression. After the paper is peeled away, the eyes are drawn in to complete the work. This method is simple, but it is not suited for detailed expression. However, it is said that the blurring and rubbing that occur by chance create a unique taste for each individual print.

©Shohei Kumano

The indirect method is said to have been adapted from Chinese ink-rubbing techniques. Dampened Japanese paper is pressed over the fish, and the surface is lightly tapped with a pad soaked in ink or pigment. This method allows shading and coloration, greatly expanding the range of expression.

Although it is technically more difficult, the use of multiple colors makes it possible to achieve results that resemble fine artwork.

©SubaruWorkshop

In both methods, it is customary to add the angler’s name, the name of the fish, its weight, and the date, so that the gyotaku serves as a complete record of the catch.

The Development of Gyotaku: From Ink to Color, Digital, and Art

Gyotaku began as monochrome prints made with black ink. Used to accurately preserve the results of fishing, it later developed into color gyotaku, where pigments were added to make the fish’s body appear more vivid. In the modern era, digital gyotaku has emerged, created by cutting out the fish image from a photograph and printing it onto Japanese paper or cloth. By ordering from specialized companies, anyone can now produce gyotaku without having to master the techniques themselves. Furthermore, through the activities of groups such as Tatsunoko-kai and Takushō-kai, works that make full use of color and the element of chance are now being created, and gyotaku has come to be appreciated as art with cultural value.

Colum:Web Gyotaku as a Modern Slang Term

In modern Japanese internet culture, the word “gyotaku” is also used as slang. Web gyotaku originally referred to a service that saved snapshots of web pages, and from there it spread as a general term for preserving online evidence【WebGyotaku】.

Gyotaku and Western Taxidermy

In the West, beginning in the nineteenth century, it became common to preserve fish as taxidermy specimens. Taxidermy preserved the shape and color as they were, serving as proof of fishing or hunting achievements. In Japan, however, gyotaku developed, leaving a record not through the actual body but by transferring its impression. After a gyotaku is made, the fish is thoroughly washed and eaten, which shows a different sensibility. This may not exactly be the same as the idea of mottainai, but it reflects an attitude of not wasting the life of what has been taken as food, and of paying respect to it.

This is not to say that Western taxidermy is negative. In Europe, through the Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo periods, realistic painting techniques flourished. Preserving things in their exact form was considered culturally refined, and in that context, taxidermy was naturally accepted. In this way, gyotaku and taxidermy can be seen as two different methods born from distinct cultural backgrounds, reflecting how people chose to preserve their encounters with nature.

Experiencing Gyotaku

Gyotaku can still be experienced today. Representative organizations include “Art Gyotaku Tatsunoko-kai” and “Art Gyotaku Takushō-kai.”

| Organization | Location | Schedule | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Art Gyotaku “Tatsunoko-kai” | Ochanomizu (Dentsu Kaikan), Yokohama (YWCA) | Twice per month | Fish, paints, and paper are provided. Beginners are welcome, and observation and membership are accepted at any time. |

| Art Gyotaku “Takushō-kai” | Various locations (announced in advance) | July 12, 27; September 13, 27; October 11, 26; November 1, 16; December 7, 21, 2025 | 9:30 AM – 4:30 PM. Attendance and whether fish are needed must be reported to Chairman Moriuchi by the Thursday immediately before the class. |

※Information as of 2025.

By participating in these classes, people can learn the direct method or colored gyotaku and create their own works. It provides a chance to experience the charm of gyotaku firsthand, where each print reveals unique expressions created by chance.

Gyotaku Today

Gyotaku took shape in the Edo period, when samurai, living in a peaceful age, sought both discipline and recreation in fishing. The oldest surviving work, “The Crucian Carp of Kinshi-bori,” remains as proof of its early history. From ink to color, digital, and art, gyotaku has transformed its form while continuing to be handed down as a culture that combines record and artistry. Even today, it continues to attract many people.

You might also be interested in these articles

■Wabori: The Tattoo Art Japan Tried to Hide

Editor and writer from Japan. Not the best at English, but I share real stories with heart and honesty — aiming to connect cultures and ideas that matter.