The Nobel-Winning Theorem Solved 100 Years Early

Can you solve this problem?

In Edo-period Japan, ordinary townspeople and samurai alike competed to solve advanced mathematical puzzles and dedicate their solutions on wooden tablets called sangaku at Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. These tablets weren’t just academic exercises—they were a blend of art, competition, and community entertainment.

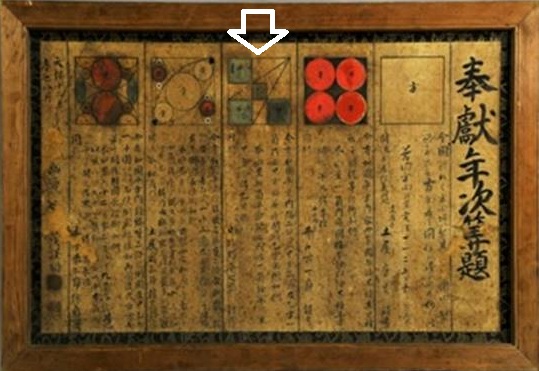

This sangaku problem was posed in 1841 by an 11-year-old boy named Hibino Heinosuke. Ready to test yourself against a math prodigy from two centuries ago?

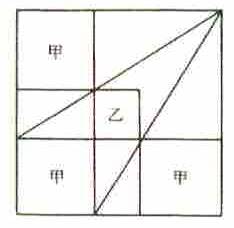

Problem:

Inside a large square, diagonal lines create three identical small squares labeled “A” and one different square labeled “B.” Given the side length of square A, find the side length of square B.

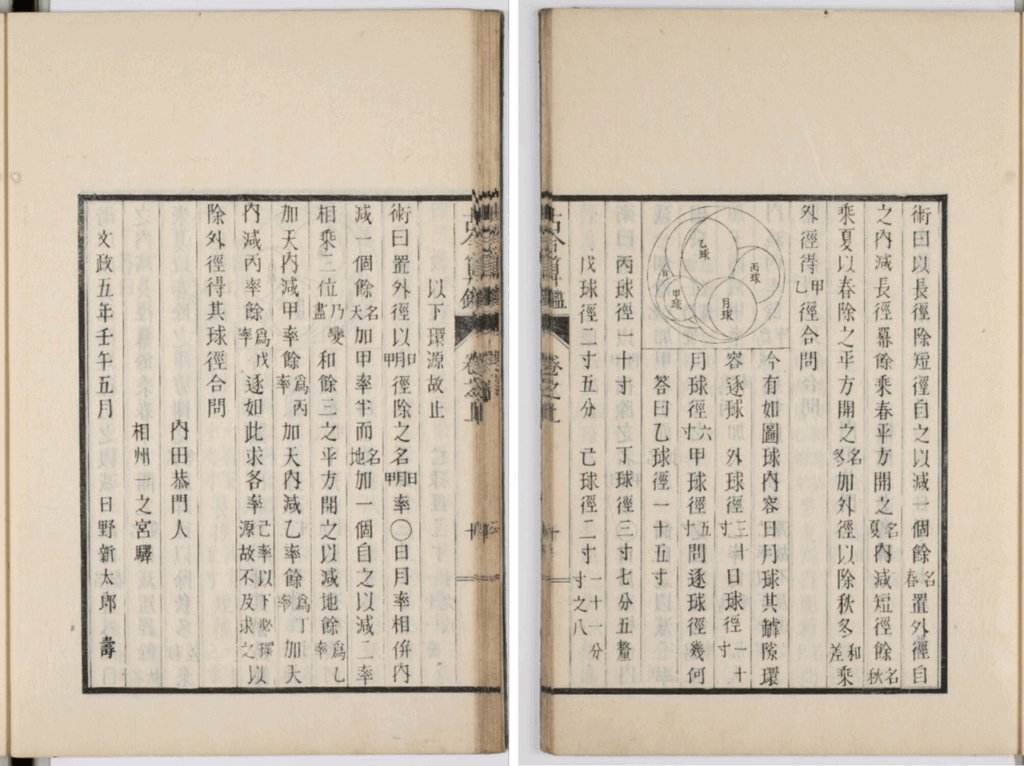

Answer:

Did you catch that? The formula uses (√5 − 1)/2, which is the golden ratio—meaning this elegant solution connects Japanese temple math with a universal constant still revered in modern mathematics.

Mathematics Advancing in Parallel with the West

While Europe was entering its golden age of mathematics—with Isaac Newton (1642–1727) and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) establishing calculus, which would later be refined by Bernoulli and Euler—Japan was developing its own unique tradition. From the 14th to 16th centuries, the abacus (soroban) spread throughout the archipelago, sparking a widespread interest in calculation. By the Edo period (1603–1868), mathematical literacy had advanced far beyond basic arithmetic: thanks to figures like Seki Takakazu, ordinary townspeople were solving simultaneous equations and tackling advanced geometry.

This vibrant “wasan” culture enabled merchants, samurai, and even farmers to master complex math independently of the West. Calculation contests were popular, and local math schools helped spread knowledge to every corner of Japan. The result was a society where even commoners engaged in sophisticated problem-solving.

Places of Learning: Terakoya and Private Juku Schools

In Edo-period Japan, education was not a monolithic system. Basic literacy, numeracy, and moral education were typically taught at terakoya—small temple-run schools open to children of commoners. Here, both boys and girls could learn reading, writing, and elementary arithmetic using the abacus (soroban).

For those who completed terakoya or wished to pursue more advanced studies, there were private juku (academies) specializing in subjects like wasan (traditional mathematics), Chinese classics, or kokugaku (national learning). Some juku offered sophisticated courses in algebra, geometry, and astronomical calculations. In farming villages, wealthy farmers often organized study groups that functioned like local wasan schools.

These diverse educational opportunities meant that both urban and rural children—at least those from families who could afford it—had access to increasingly advanced mathematical training. Through this multilayered system, sophisticated knowledge spread well beyond the samurai class, nurturing a unique culture in which solving complex math problems became a hobby and a mark of refinement.

What Are Sangaku? The Math Challenges Dedicated at Shrines

Sangaku refers to the practice of writing difficult mathematical problems that people have solved or puzzles that they have created on votive plaques and dedicating them to shrines and temples. Like votive plaques that pray for health and good fortune, it was a popular custom of praying for academic success.

During the Edo period, the study of mathematics was considered a sophisticated hobby on a par with other arts such as the tea ceremony and flower arranging. From urban cram schools to rural gatherings, people from all walks of life – samurai, merchants, women and children – studied and competed in advanced geometry and algebra.

When someone solved or invented a difficult problem, they could view the votive plaque hanging in the shrine grounds and attempt to solve it themselves, and if they could not solve it, they could return to the cram school to learn more. This created a cycle of learning and challenge, fostering a vibrant culture of mathematical inquiry throughout the community.

The Nobel-Winning Theorem Solved 100 Years Early

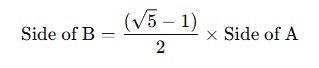

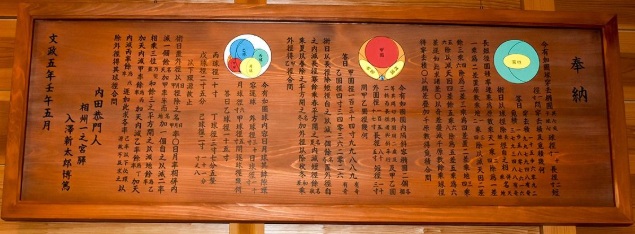

One of the most astonishing stories in wasan history involves the “Hexlet Theorem.” In 1936, British chemist Frederick Soddy published this result in Nature, describing a necklace of six spheres touching each other and two other fixed spheres inside a larger sphere—known today as Soddy’s Hexlet. Soddy’s name became attached to the theorem, and he even won the Nobel Prize in 1921 for unrelated work on isotopes.

But almost 100 years before Soddy’s publication, in 1822, a Japanese merchant and wasan devotee named Irisawa Shintarō Hiroatsu dedicated a sangaku at Samukawa Shrine in Sagami Province (modern Kanagawa). His problem described exactly the same six-sphere configuration, with a complete proof. Irisawa, descended from Omi merchants, sold tea, textiles, and herbal medicines—and solved world-class math problems in his spare time.

Although Irisawa’s sangaku itself was lost, his teacher Uchida Itsumi recorded the problem and its solution in the 1832 book Kokon Sankan. A recreated sangaku based on that record is displayed today at Samukawa Shrine, offering living proof of Japan’s mathematical brilliance during the Edo period.

Wasan as Practical Math: How It Supported Society

Sangaku tablets symbolize the playful and artistic aspects of Wasan, but Wasan in the Edo period also had a deep practical value. We will introduce four areas of Wasan that were directly useful in everyday life.

- Agriculture and Irrigation

Farmers and local mathematicians used wasan techniques to design irrigation canals and reservoirs. Innovators like Ōhata Saizō in the 17th century calculated land gradients and soil volumes, even inventing tools like the suijoudai (leveling device) to ensure precise water flow. His 24-kilometer-long Fujisaki Canal still supports farming today. - Civil Engineering and Taxation

Officials relied on wasan for measuring land, calculating rice yields, and determining fair taxes. These “chihō sanpō” (local arithmetic methods) were critical in managing villages and ensuring efficient tax collection without sparking uprisings. - Calendars and Astronomy

Shogunate-appointed mathematicians like Shibukawa Shunkai (1639–1715) used advanced wasan to correct errors in the centuries-old Chinese calendar. Shunkai’s accurate observations and calculations led to Japan’s own calendar system, the Jōkyō Calendar (1685), ending an 800-year-old reliance on outdated Chinese methods. - Merchant Calculations and Daily Commerce

In bustling cities like Edo and Osaka, merchants used the abacus and wasan formulas to manage complex trade. Books like Yoshida Mitsuyoshi’s Jinkōki taught methods for calculating square and cube roots—essential for everything from sake barrel volumes to exchange rates.

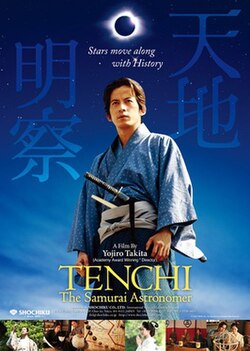

💡Column: Tenchi Meisatsu – A Window into Edo Math Culture

If you want to feel what it was like to be a mathematician in the Edo period, there’s no better place to start than Tenchi Meisatsu (literally “Insight into Heaven and Earth”), a historical novel by Ubukata Tow. Based on the life of Shibukawa Shunkai, the book vividly depicts the intense passion, rivalries, and discoveries of Japan’s calendar reform. It shows how mathematics was both a science and an art woven into the lives of samurai, merchants, and commoners.

The novel was adapted into a live-action film in 2012, bringing to life the struggles of Shunkai and his quest to create a Japanese calendar accurate to Japan’s own skies. Although there’s no official English translation yet, the book and movie give a rich glimpse into the world of wasan and the spirit of the people who devoted themselves to numbers under the shogunate’s rule.

Experience It for Yourself

In recent years, young Japanese mathematicians have begun to revive the tradition of dedicating mathematical tablets. In 2018, Rosalie Hosking, together with volunteers from the University of Canterbury, became the first foreigner to dedicate a mathematical tablet to Kitano Tenmangu Shrine in Kyoto. If you visit Japan, why not try looking for mathematical tablets at shrines and solving ancient problems for yourself? You may find new reasons to love shrines and temples beyond their beauty and history.

Would you like to experience the thrill of solving a 200-year-old math challenge? Try tackling a sangaku next time you visit a shrine—and discover the joy that once captivated Edo-period minds.

You might also be interested in these articles

■Japan’s Factory Tours Are Free. But You Probably Won’t Leave Empty-Handed.

Editor and writer from Japan. Not the best at English, but I share real stories with heart and honesty — aiming to connect cultures and ideas that matter.