Gothic & Lolita: A Japanese Fashion Where Dream and Darkness Collide

What Is “Gothic & Lolita”?

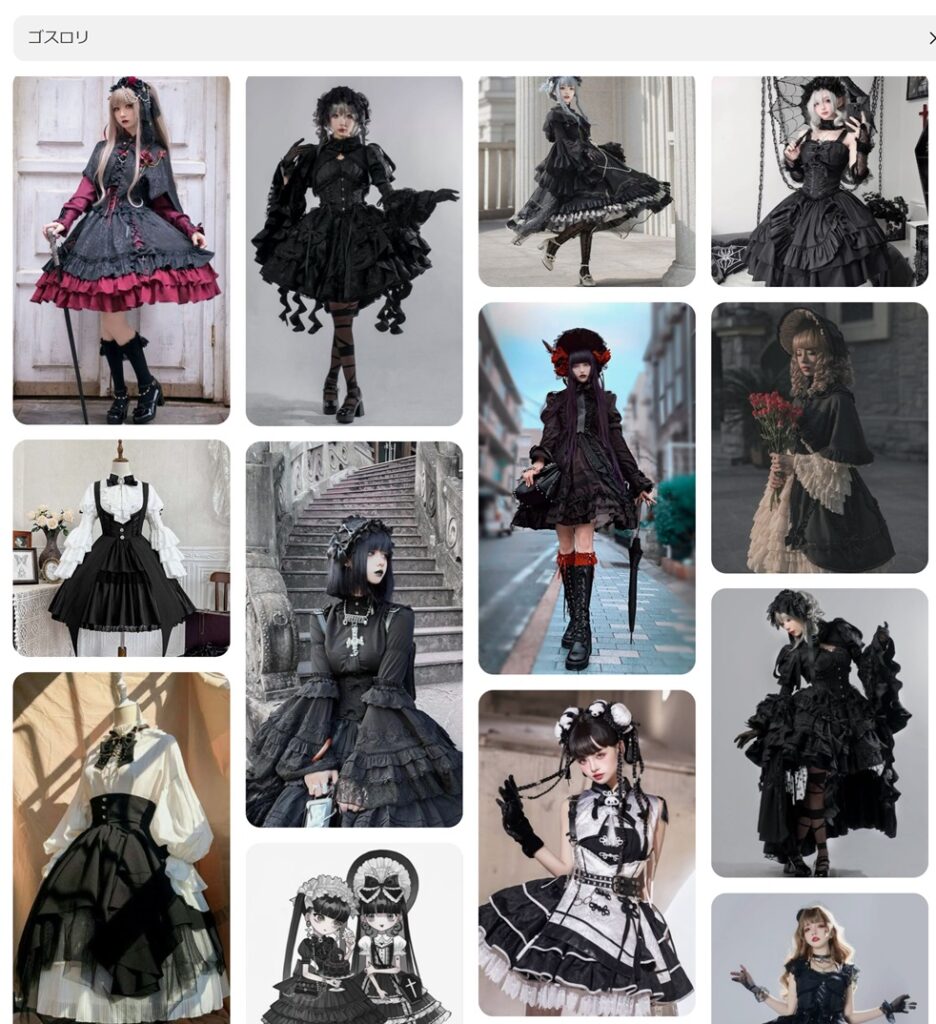

Gothic & Lolita—often shortened to “GosuLoli” in Japan—is a fashion style that blends the frilly innocence of Lolita fashion with the dark, romantic aesthetic of Gothic culture. Think puffed skirts, lace gloves, crosses, corsets, parasols… and layers of symbolism.

The term itself can be a bit confusing. Strictly speaking, Gothic Lolita is just one substyle of the broader “Lolita fashion” category. But in everyday Japanese use, “Gothic & Lolita” or “GosuLoli” is often used more loosely to refer to Lolita fashion in general. This article uses both interpretations while focusing on the cultural roots and deeper meanings behind the style.

A Look Back: From Romantic Nostalgia to Subcultural Statement

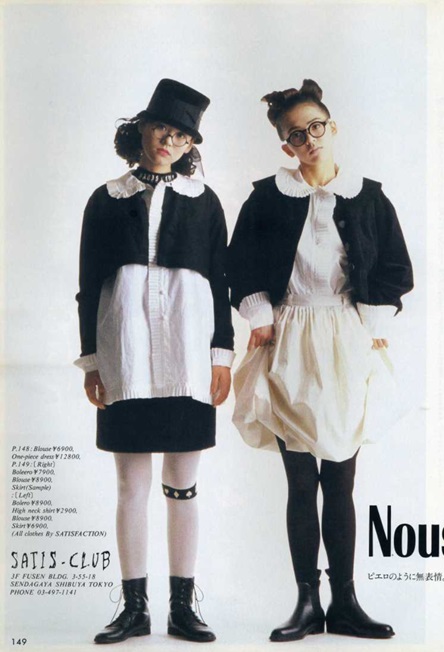

Lolita fashion first began to take form in Japan in the late 1970s and 1980s. Influenced by Rococo and Victorian aesthetics, it emerged as a response to Western trends that dominated Tokyo’s youth culture at the time.

Boutique brands like MILK, Shirley Temple, and Jane Marple started offering clothes that were frilly, girlish, and nostalgic—blending old European charm with Japanese street fashion flair.

At the same time, magazines like Olive and CUTiE promoted DIY spirit and “mismatch styling,” encouraging young women to mix and personalize their looks rather than follow runway trends. These girls weren’t dressing to please anyone but themselves.

It wasn’t called “Lolita fashion” yet—but the seeds had been planted.

The Rise of Gothic Lolita: Music, Literature, and Visual Power

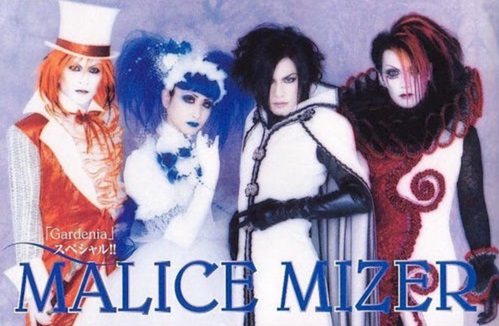

In 1999, Japanese guitarist Mana, known for his work with the visual kei band Malice Mizer, founded a fashion label called Moi-même-Moitié. His brand fused religious and Gothic motifs with Victorian silhouettes, launching what he named Elegant Gothic Lolita (EGL) and Elegant Gothic Aristocrat (EGA). It gave rise to what is now known as “Gothic Lolita.”

Around the same time, writer Nobara Takemoto—a major voice in early Lolita subculture—promoted what he called the “Otome spirit”: a way of life rooted in fragility, beauty, and defiance. His books and interviews helped shape the idea that wearing Lolita wasn’t just fashion—it was philosophy.

Right: “Kamikaze Girls,” which he wrote the original story.

Manga artist Mitsukazu Mihara added her voice through hauntingly beautiful illustrations in series like DOLL, further defining the melancholic Lolita aesthetic. Ball-jointed dolls (like Super Dollfie), with their porcelain skin and delicate dresses, also became visual icons within the community—representing a fragile, untouchable ideal.

A Counter to the Male Gaze: Who Owns “Girlhood”?

The term “Lolita” carries heavy baggage in the West. It evokes images of sexual precocity, thanks to Nabokov’s novel and Kubrick’s film. But Japanese Lolita fashion reclaims the word and gives it a new meaning: not sexual, but self-defined.

with a girlish vibe from a man’s point of view

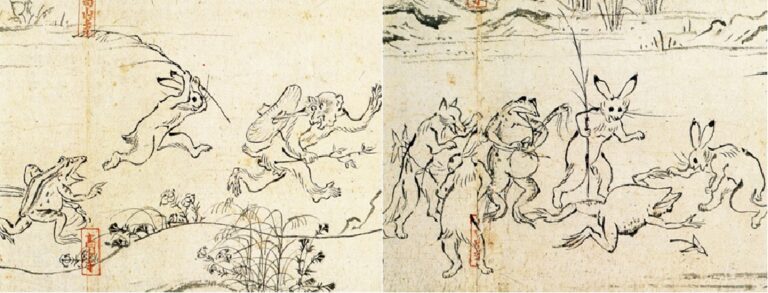

Historically in Japan, the image of “shōjo” (少女, or “girl”) was constructed through male-dominated media, literature, and illustration—from Meiji-era schoolgirl magazines to mid-century art by male illustrators. Girls were expected to be pure, pretty, and passive.

Lolita fashion rebels against that. It refuses to grow up, refuses to be consumed, and refuses to conform.

Wearing these clothes isn’t about being seen—it’s about seeing yourself in the mirror and smiling. It’s not for men. It’s not even for society. It’s for you.

The Philosophy Behind the Frills

Lolita fashion isn’t cosplay, and it’s not about nostalgia. At its core, it’s a form of emotional armor. You wear lace and petticoats not just to feel cute—but to create a personal world that protects you from the outside.

“When you wear these clothes, I want you to become the kind of girl who fits them. The way you speak, move, and think—it all matters.”

—Nobara Takemoto

“Gothic Lolita is for those who can love a mysterious, timeless worldview beyond fleeting trends.”

—Mana

The style often reflects both fantasy and solitude. Beneath the frills lies heartbreak, escape, strength, and tenderness. And for many, it becomes a way to live—not just a way to dress.

Where to Find It: Brands Still Defining the Scene

Though the mainstream spotlight has shifted over the years, Gothic & Lolita fashion is still very much alive—especially within online and global communities. Some leading brands include:

- Moi-même-Moitié — Founded by Mana; known for religious and aristocratic Gothic styles.

- Atelier Pierrot — Elegant, corset-heavy designs with dramatic flair.

- BABY, THE STARS SHINE BRIGHT / Alice and the Pirates — Blends sweet Lolita with dark fantasy.

- Angelic Pretty — Iconic for sugary pastels and dreamy motifs.

- h.NAOTO — Combines Gothic fashion with punk and streetwear.

Many of these brands have shops in Tokyo’s Harajuku and Ikebukuro districts, but they also sell internationally online and through fashion events around the world.

Changing Tides: From Harajuku to Hashtags

In the early 2000s, Lolita fashion was easy to spot on the streets of Harajuku. But in recent years, those sightings have become rarer—not because the style disappeared, but because it changed.

Today, Lolita intersects with anime culture, “Jirai-kei” (a moody, provocative aesthetic), and social media-driven microtrends. Online tea parties have replaced in-person meetups. Community hubs have moved from Harajuku to places like Akihabara and Ikebukuro. And while Japan’s Lolita population may be shrinking, global interest is rising.

From Muslim girls creating “Hijabi Lolita” styles to fans in Paris, New York, and Shanghai organizing fashion shows—Lolita has become a worldwide language of expression.

Dressing as a Form of Resistance

Gothic & Lolita isn’t about looking cute or pretty. It’s about claiming space—emotionally, visually, philosophically.

It’s about dreaming on your own terms.

It’s about choosing softness when the world demands hardness.

It’s about becoming a version of yourself that only you can define.

And above all, it’s about wearing that version proudly—frills, shadows, and all.

Erika Nishizono here — a lover of traditional kimono, modern art, and all things beautiful. Exploring how style and culture shape the way we live.