How Edo Boys Got Drip?

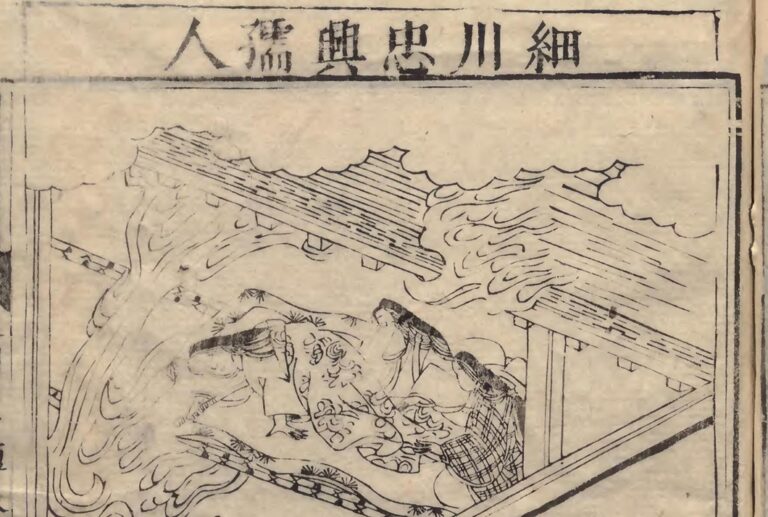

Modern Japanese men are often considered fashion-forward, but their Edo-period ancestors might have outdone them when it comes to commitment to style. One remarkable testament to this is the illustrated style manual Tōsei Fūzoku Tsū (“Contemporary Customs Illustrated”), published in 1773.

At first glance, it may look like a historical document, but in reality, it’s essentially a style guide for men preparing for a night out at the pleasure quarters. Each featured style is associated with a different social class, showing us that fashion trends weren’t just for the rich and powerful—they were a cultural norm that extended across the spectrum of Edo society.

Four Distinct Styles, Four Distinct Social Roles

Reimagined as modern men’s fashion magazine covers, the following styles reflect more than clothing—they express identity, class, and personal flair.

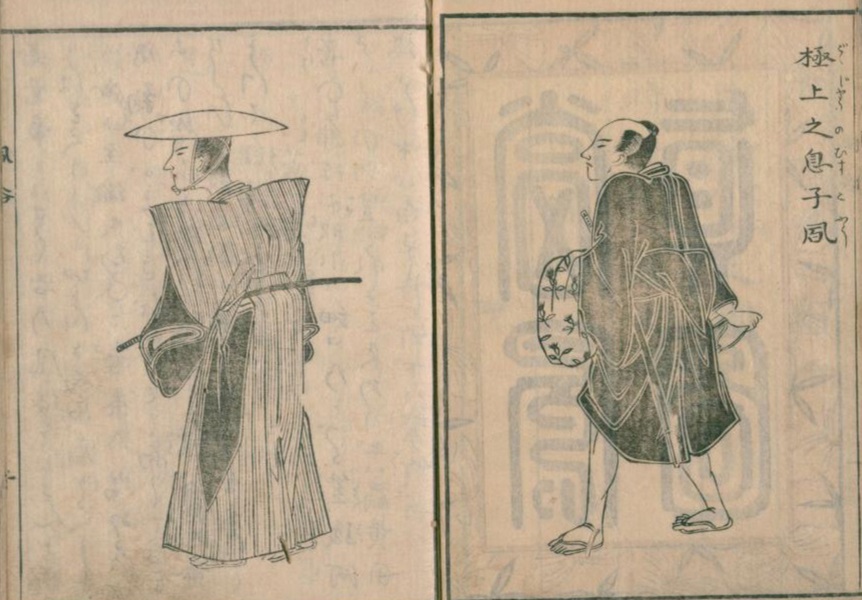

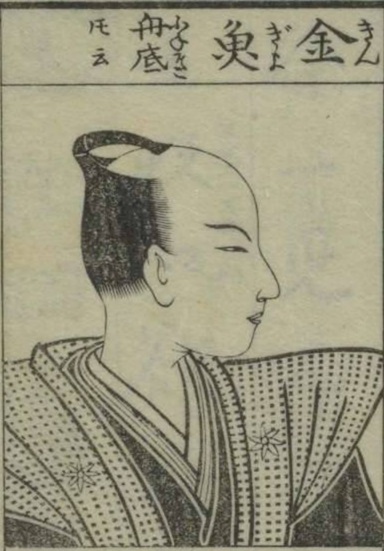

Style 1: GQ JAPAN — “Gokujō no Musuko” (Elite Sons of Samurai)

- The clean, dignified look favored by upper-class samurai and the sons of lords.

- Quality fabrics in subdued tones, well-kept chonmage topknots, and immaculate folding.

- An air of quiet confidence—the kind of look that makes you stand out by not trying too hard.

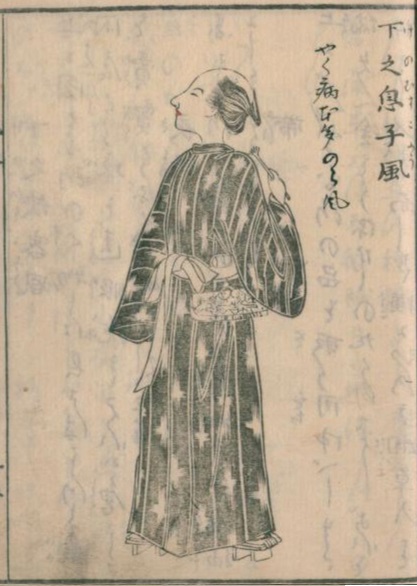

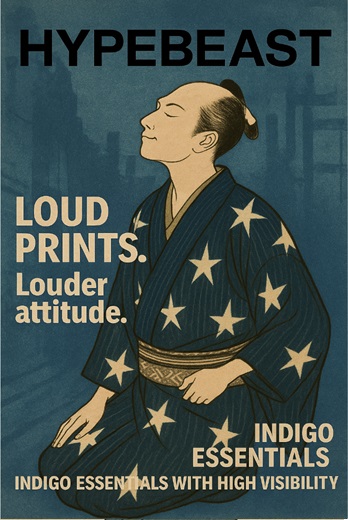

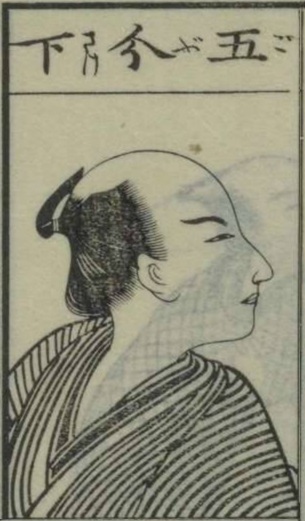

Style 2: HYPEBEAST — “Shimo no Musuko” (Lower-Class Ronin and Townsmen)

- Bold prints, flashy colors, loosened kimono robes.

- A streetwear aesthetic before streetwear existed—expressive, defiant, full of attitude.

- Self-styled fashion that speaks louder than any formal code.

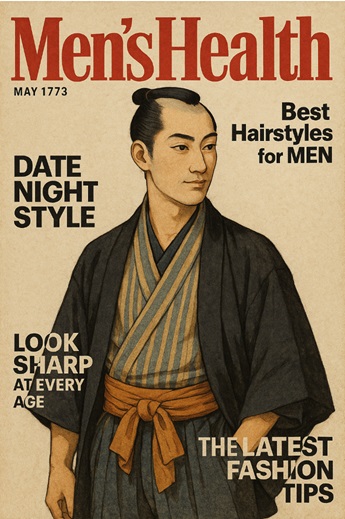

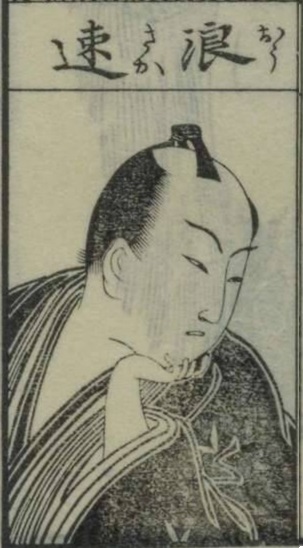

Style 3: Men’s Health — “Chū no Musuko” (Working-Class Apprentices and Laborers)

- Practical yet polished; ideal for young men working in shops or assisting with household tasks.

- Neat sandals, balanced layering, and thoughtful details.

- Designed for movement, but never at the cost of form.

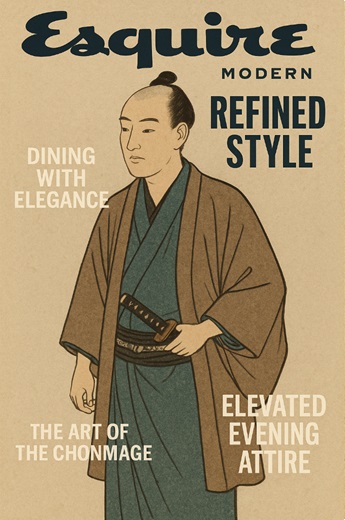

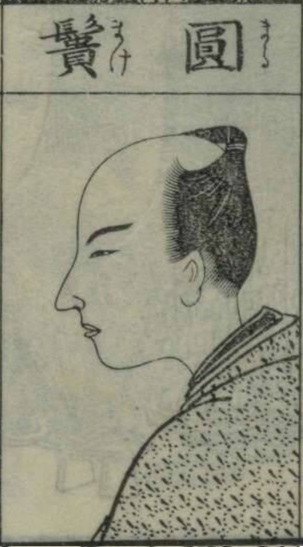

Style 4: Esquire JAPAN — “Ue no Musuko” (Lower-Ranking Samurai or Cultured Commoners)

- Discreet elegance with understated color coordination.

- Emphasis on small accessories: a fan, a pouch, or a subtly patterned sash.

- Ideal for those who wanted to appear worldly without overstepping their station.

Historical Context: The Year 1773

Tōsei Fūzoku Tsū was published in An’ei 2 (1773), during a period of relative peace under the Tokugawa shogunate.

This was an era when merchant classes were rising in influence, and urban culture was thriving. With no major wars to fight, samurai and townsmen alike turned their attention to culture, aesthetics, and social expression.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the Rococo movement was in full swing among aristocrats, with powdered wigs, embroidered frock coats, and elaborate lace. Working-class Europeans, however, dressed plainly in coarse linen or wool.

Edo Japan differed in that even townspeople pursued fashion according to social codes, developing their own styles that signaled status and identity within their means.

souce:Wikipedia

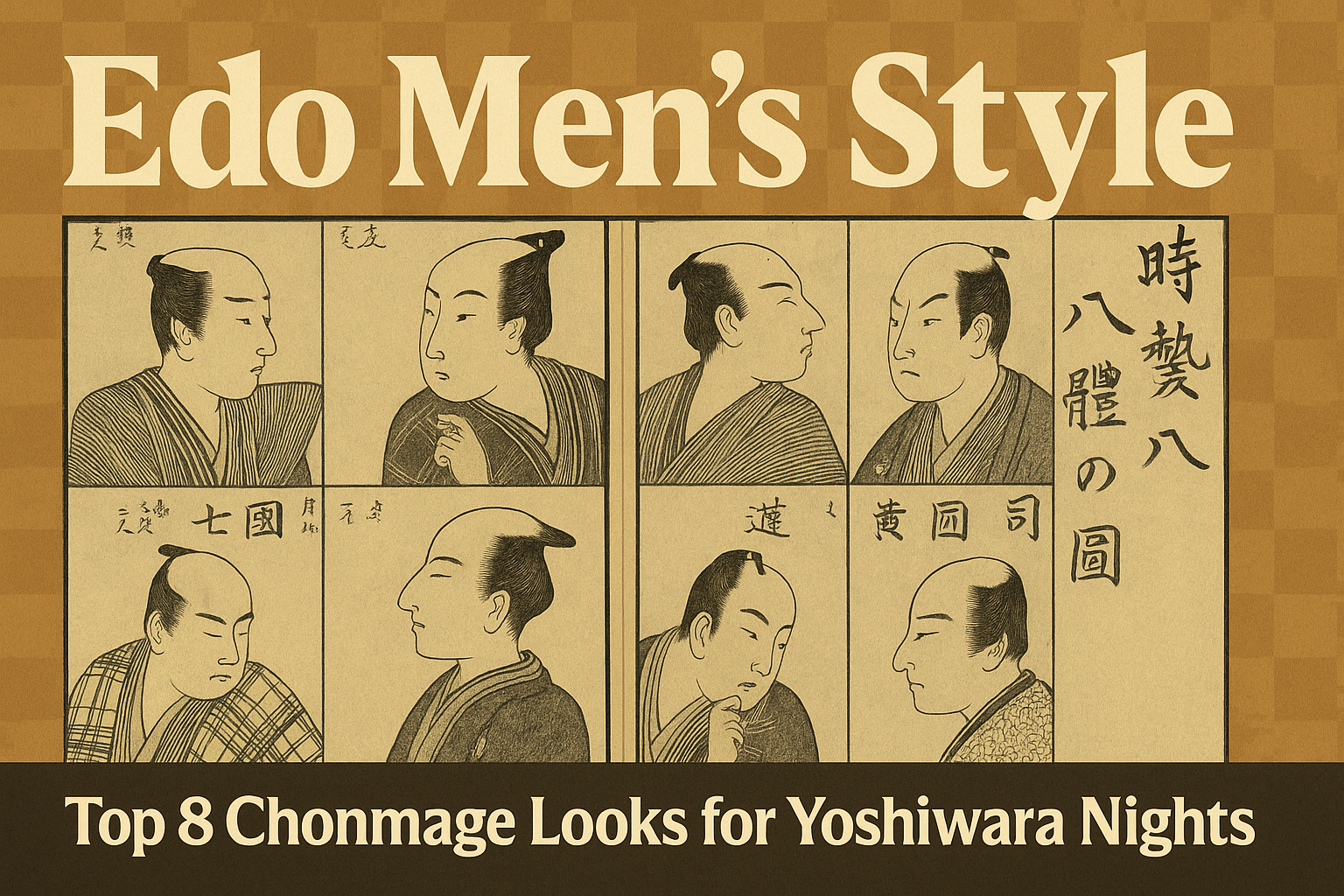

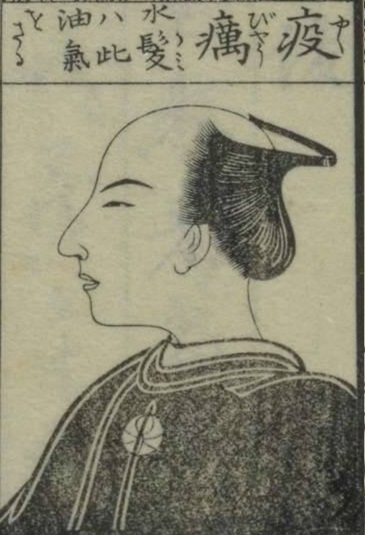

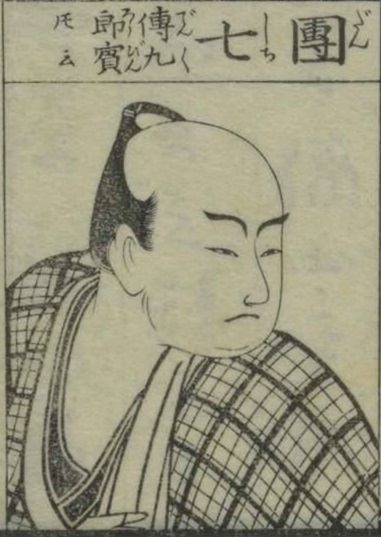

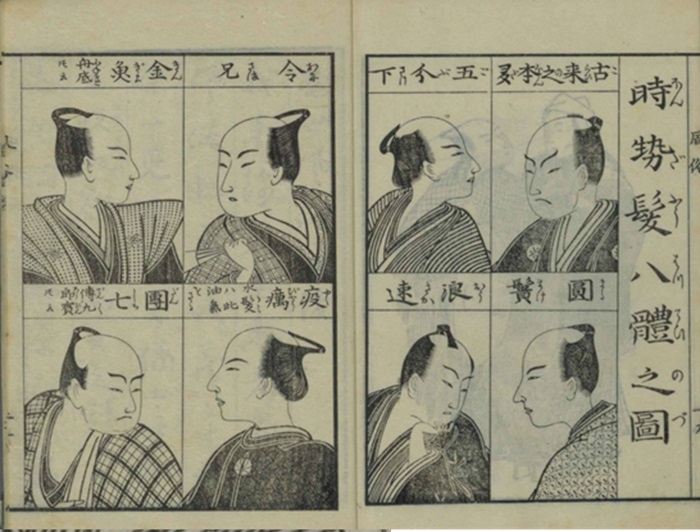

The Samurai’s Style Secret — Chonmage Hairdos

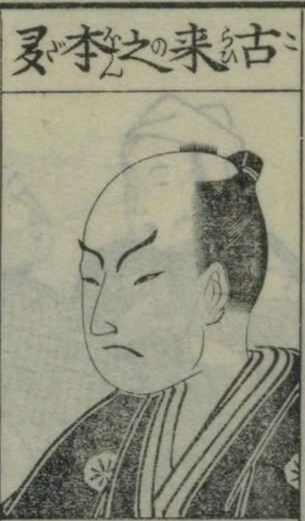

The first thing that grabs your attention in samurai fashion? The iconic chonmage.

This distinctive topknot may be the world’s longest-running hairstyle trend. It began as a practical way to keep cool under battle helmets. Yet even in peacetime, the look evolved—and endured.

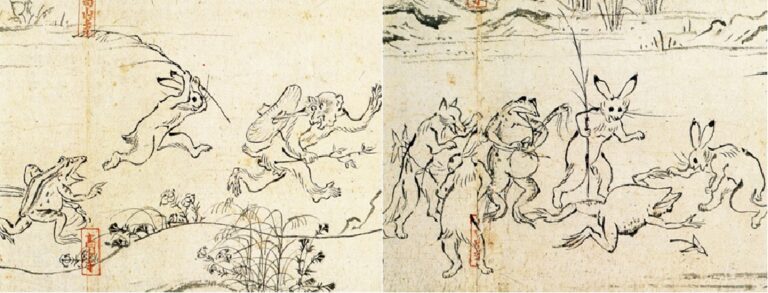

While chonmage may appear similar at first glance, the Edo period saw a growing variety of styles, especially among men heading to Yoshiwara. The same guide, Tōsei Fūzoku Tsū, includes a spread titled “Eight Popular Hairdos,” all built on the popular Hondamage foundation but creatively adapted.

These hairstyles were essentially all built upon the popular Hondamage style, but each had its own unique twist.

What these styles show us is that fashion isn’t just about clothing—it’s a system of signs. Even in an era without Instagram, men of Edo found creative ways to express identity, status, and charm through a twist of hair and a tuck of cloth.

Each hairstyle carried coded messages—about the wearer’s role, status, or even which house of pleasure he frequented.

They Wore More Than Clothes—They Wore “Iki”

“Iki” (stylish modesty) was about more than appearance—it was about knowing your place and still expressing refinement and flair.

Edo-period men used clothing not only to signal class and respect but also to engage in aesthetic rivalry and social performance.

Time may have passed, but the question remains the same: “How do I present myself?”

And that’s why Edo men’s fashion still resonates today.

Edo Men’s Fashion is not dead. It never was.

“Tosei Fuzoku Tsu” (owned by the Nara Women’s University Academic Information Center)

Source: National Book Database

You might also be interested in these articles

■Ninja Snipers and the Truth Behind the Nobunaga Assassination Attempts

Erika Nishizono here — a lover of traditional kimono, modern art, and all things beautiful. Exploring how style and culture shape the way we live.