Kabuki: The Living National Treasure of Japan’s Performing Arts

In 2025, the film Kokuhō (National Treasure) was screened in the Directors’ Fortnight section of the Cannes Film Festival, reminding audiences around the world of the word kabuki.

Directed by Lee Sang-il and starring Ryō Yoshizawa and Ryūsei Yokohama, the film depicts the inner world of those who “live for their art.”

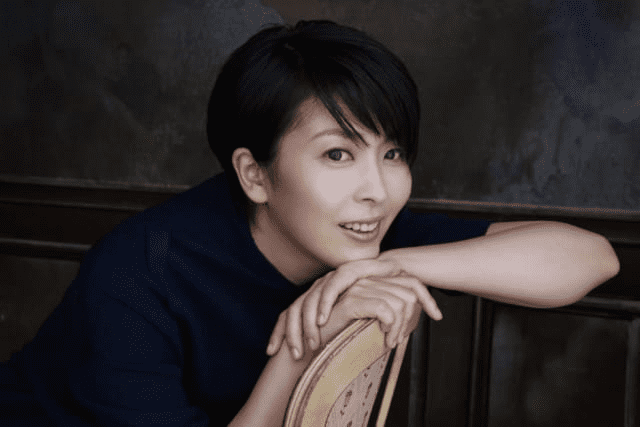

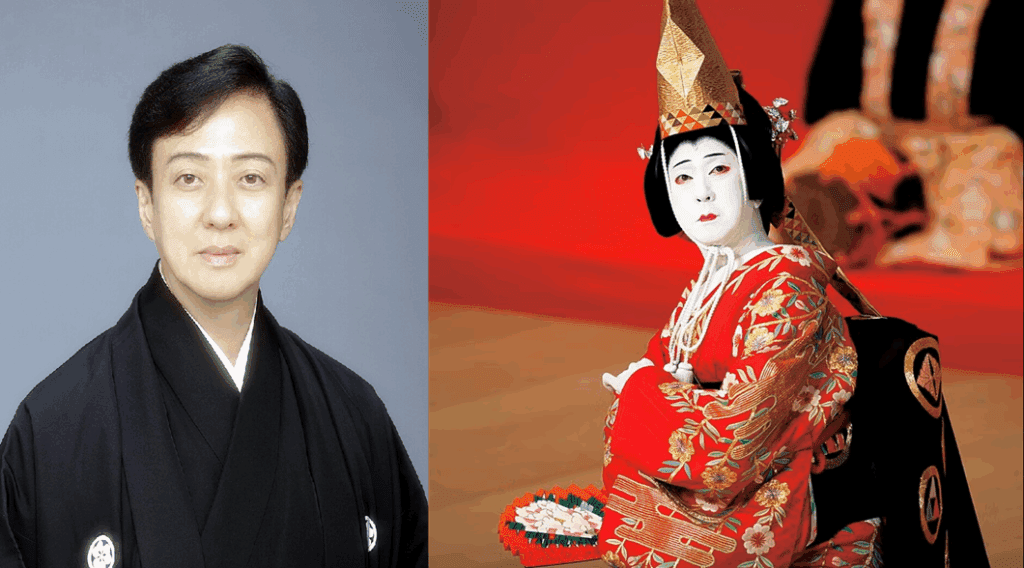

Photo: film Kokuhō (National Treasure)official website

While it shows the brilliance of the stage, its true focus lies not on kabuki itself but on the solitude and pride of those who inherit the stage name and carry the weight of their lineage.

And the mirror that reflects such hearts is Japan’s traditional performing art that has lasted for over 400 years — Kabuki.

What Is Kabuki — A Comprehensive Performing Art with a 400-Year History

The word kabuki comes from kabuku (傾く), which literally means “to lean or deviate.”

It referred to those who defied convention and authority — the kabukimono, people who lived in a way that was eccentric and rebellious.

That spirit took form as a performing art in 1603, when Izumo no Okuni began kabuki odori (kabuki dance) in Kyoto.

Her free spirit and flamboyant costumes fascinated audiences, and the art flourished among the common people.

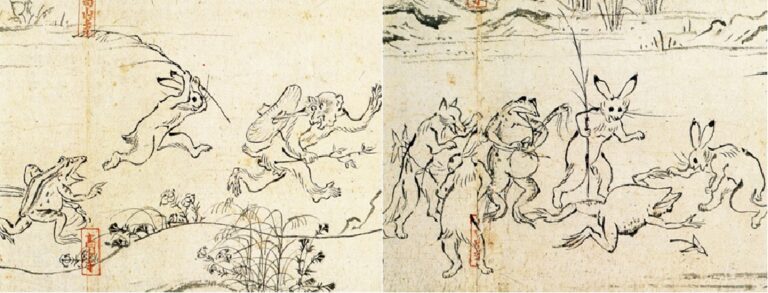

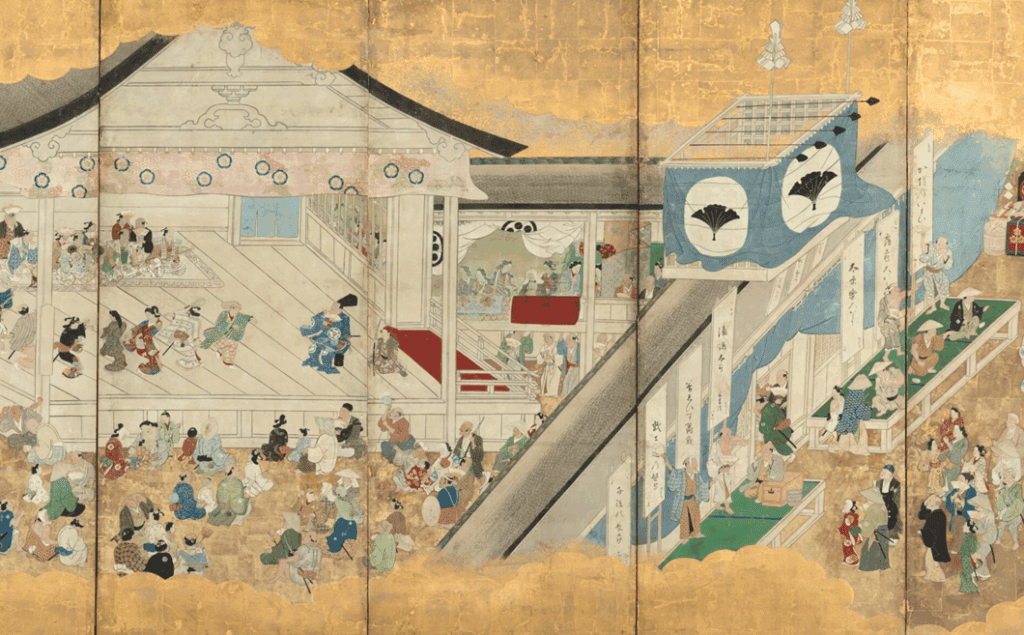

By Hishikawa Moronobu, 17th century

Tokyo National Museum

Later, onna kabuki (female kabuki) performed by courtesans and wakashu kabuki (adolescent boys’ kabuki) became popular, but both were banned by the shogunate for corrupting public morals.

Thus emerged yarō kabuki (men’s kabuki), in which adult men performed all the roles, leading to the birth of onnagata — male actors who play female roles.

This transformation established the foundation of the kabuki we know today.

Kabuki combines drama, dance, and music into a comprehensive art form.

The stage is designed like a painting, and every movement is calculated like architecture.

The bold kumadori face paint, elaborate costumes, and the walkway known as hanamichi are all crafted to guide the audience’s emotions.

Unlike nō or kyōgen, kabuki was nurtured not by the ruling class but by the townspeople — that independence remains one of its defining features.

Those Who Inherit — The Drama of Family and Bloodline

To understand kabuki, one must understand succession and stage names (myōseki).

Actors carry the names of their yagō (stage houses) such as Naritaya, Nakamuraya, or Otowaya, and inherit their styles from generation to generation.

These families are collectively known as Rien (梨園), literally “the pear garden,” a term that originated from a Chinese legend where the emperor gathered performers in a pear orchard.

In Japan, it refers to families and lineages devoted to the performing arts.

Children born into kabuki families make their first stage appearance as early as three to five years old.

This debut is less a “career start” than a ritual of inheritance, where they breathe the air of the stage and absorb the rhythm of the audience.

Each house has its own specialty:

Naritaya (the Ichikawa Danjūrō family) is known for aragoto (rough, heroic acting);

Nakamuraya for sewamono (domestic human dramas);

and Otowaya for realistic, refined performances.

Each family hones its distinct oie-gei (house art), passed down like a living DNA of craft.

In kabuki, art is not the property of the individual but the soul of the family itself.

However, this system can also feel like a burden of blood.

Children born to inherit a name grow up with duty that outweighs personal freedom —

a reality reflected in Kokuhō, where art and blood are bound together.

There is also another reality: women cannot perform on the kabuki stage.

Actresses such as Takako Matsu (known for Confessions and The Third Murder, both available internationally on Netflix, and later for the Netflix drama My Dear Exes)

and Shinobu Terajima (acclaimed for Vibrator and Oh Lucy!, and appearing in the 2025 film Kokuhō)

were born into Rien families but found their own paths as actresses outside the kabuki world.

Their performances still carry the timing and formality of kabuki’s kata (forms) and ma (rhythmic pauses).

At the same time, the tradition of onnagata — men performing women’s roles — continues.

Thus, the paradox remains: men play women, while women cannot appear on stage.

This aesthetic of contradiction gives kabuki its unique philosophical depth.

Modern Kabuki — Technology and Translation to the World

Modern kabuki is not merely about preservation but about constant reinvention.

A prime example is Super Kabuki, created in 1986 by Ichikawa Ennosuke III.

This style retains classical forms while integrating modern stories and pop culture.

It began with Yamato Takeru and, in 2015, brought One Piece to the stage —

expressing the spirit of friendship and justice through kabuki’s own vocabulary.

Foreign audiences often attend these shows, aided by English subtitles and live narration.

.png)

(C) Eiichiro Oda/Shueisha, Super Kabuki II “One Piece” Partners

In fact, kabuki’s globalization started long ago.

The first overseas performance took place in 1928 in the Soviet Union.

In 2004, Nakamura Kanzaburō brought his portable Heisei Nakamura-za theater to New York,

and in 2009, Yukio Ninagawa’s NINAGAWA Twelfth Night captivated London audiences.

Today, theaters like the Kabuki-za in Ginza offer English earphone guides and online reservations.

Tradition, now translated and subtitled, continues to open itself to the world.

Change is not betrayal; tradition means performing “the present” again and again.

Experiencing Kabuki — The Audience Also Performs

Kabuki is not just to be watched; the audience also plays a part in the performance.

At the Kabuki-za Theatre in Higashi-Ginza, visitors can buy tickets for a single act (hitomakumise) for around 4,000 yen.

First-class seats cost over 20,000 yen, but wherever you sit, the impact of the hanamichi walkway remains the same.

Dress codes are flexible, yet many choose elegant kimono, making the entire theater feel like a living picture scroll.

An earphone guide (700–800 yen) is a must for understanding the context, dialogue, and highlights in real time — perfect for first-time visitors.

A pair of binoculars lets you appreciate the actors’ expressions and intricate costumes up close.

Another distinctive custom is the Ōmukō (大向う), the traditional system of kabuki cheerers.

The term originally referred to the back seats of the theater.

From these upper rows, seasoned connoisseurs call out the actors’ yagō (house names)

or phrases like “Mattemashita!” (“We’ve been waiting for this!”)

at perfectly timed moments — when an actor appears on the hanamichi, or during a mie (見得),

a dramatic, motionless pose that crystallizes emotion on stage.

These shouts are not random cheers but acts of respect and praise for the actor and the art.

A well-timed call can electrify the audience, while silence after a weak performance speaks volumes.

In kabuki, even silence becomes a form of critique.

Though the practice was historically male-dominated, more women now take part with deep knowledge and discipline.

What matters is not gender but timing, restraint, and dignity —

a voice that elevates the performance rather than disrupts it.

Ōmukō is, in essence, a “vocal art” offered from the audience to the stage.

On opening nights or name-succession performances, it is also common to see the actors’ wives greeting patrons in the lobby —

a reminder that the unseen world of Rien families is itself part of the theater.

The audience, too, sustains the stage through reverence and attention.

That unity between performers and viewers is the soul of kabuki.

Kabuki — A Living National Treasure

Kabuki is not an art preserved in glass but one that lives and breathes.

Over four centuries, it has endured countless upheavals and yet found new forms each time.

What Kokuhō captured was this very spirit.

To inherit a name, to preserve tradition, to challenge the times —

all of this is condensed into the body and voice of a single actor.

Kabuki is not a static artifact, but a living national treasure,

kept alive by human hands, voices, and souls.

You might also be interested in these articles

■Sumo Was Once a Sacred Ritual, Long Before It Became a Sport

Editor and writer from Japan. Not the best at English, but I share real stories with heart and honesty — aiming to connect cultures and ideas that matter.