Kumihimo(Silk Braids) — The Thousand-Year Art of Connecting Threads

After appearing in the movie Your Name., the red kumihimo cord has brought new attention to Japan’s traditional craftsmanship.

Kumihimo—braided cords made by intertwining fine silk threads—has been passed down for over a thousand years.

It has been used to decorate Buddhist instruments, samurai armor, and kimono accessories, and is regarded as a symbol of human connection.

Today, it continues to evolve as a form of craftsmanship found in accessories, fashion, and modern design.

What Is Kumihimo? — The Japanese Art of Braided Threads

Kumihimo (“braided cord”) is a traditional Japanese craft in which multiple threads are interlaced diagonally to create strong yet flexible cords.

Unlike woven textiles that cross threads at right angles, kumihimo is formed by intertwining threads in a three-dimensional structure, giving it elasticity and durability.

It is usually made from silk, which gives it a soft texture and natural sheen.

Photo: Kiryudo

There are several main types of braids—maru-gumi (round), kaku-gumi (square), and hira-gumi (flat)—and each is made using different types of looms such as the round stand (marudai), square stand (kakudai), or high stand (takadai).

Even when the same colors are used, the order of the threads changes the pattern entirely, resulting in unique pieces that reflect each craftsman’s skill and sensibility.

Kumihimo has long been valued not only as a practical tool, such as for fastening obi belts, but also as a symbol of “tying connections” in rituals and offerings.

The Long History of Kumihimo

The origins of kumihimo in Japan date back to the Asuka and Nara periods (7th–8th centuries), when Buddhism and continental culture were introduced from China and Korea.

Braided cords were used to bind sacred sutras and decorate Buddhist robes, symbolizing purity and devotion.

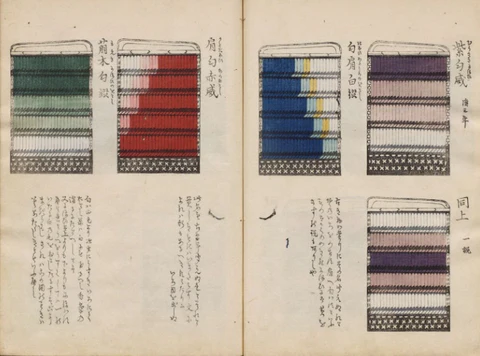

Examples such as Nara-gumi and Kara-gumi remain preserved in the Shosoin Treasury, showing the sophistication of ancient dyeing and weaving techniques.

During the Heian period, as court culture flourished, kumihimo became more decorative.

It was used for crowns, robes, scroll bindings, and accessories worn by nobles.

New techniques such as gradation dyeing and multi-colored braiding were developed to match the elegant aesthetic of the aristocracy.

In the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, as the samurai class rose to power, kumihimo became more practical.

It was used for armor laces and sword cords, and new sturdy braids such as Kikkō-gumi (tortoise-shell pattern) were invented.

The Edo period brought peace, and kumihimo flourished as part of urban culture.

It was widely used for sword cords and inrō pouches, and decorative techniques such as Ayadashi, which reveals patterns or characters on the surface, were created.

Kumihimo became a symbol of Edo’s stylish aesthetic, blending function and beauty.

After the Meiji Restoration, the abolition of the samurai’s swords caused a sharp decline in demand.

However, artisans adapted the craft for women’s obi belts, and kumihimo once again became an essential part of everyday life.

The craft continues to be handed down today through both tradition and innovation.

Two Major Centers — Kyoto and Iga

Kyoto Kumihimo (Kyokumihimo)

Born in the ancient capital, Kyoto kumihimo is known for its elegant luster and delicate, symmetrical braids.

With over 300 known patterns, it is used for obi cords, religious ornaments, and tea ceremony utensils.

Its refined colors and sophisticated beauty reflect Kyoto’s classical aesthetics.

Iga Kumihimo (Mie Prefecture)

Developed alongside samurai culture, Iga kumihimo features lustrous silk threads interwoven with gold and silver.

It is admired for its strength and three-dimensional texture.

Today, Iga produces about 90% of all hand-braided kumihimo in Japan, and its techniques are applied in both traditional obi cords and modern accessories.

Edo Kumihimo is also famous, but unfortunately it is not designated as a traditional craft. It is classified as a “traditional industry” and produces practical products, so it is different from “traditional crafts” which produce one-of-a-kind works of art.

How Kumihimo Is Made — From Silk Thread to Finished Cord

The creation of kumihimo involves many detailed, hands-on steps.

- Preparing the Threads – The craftsman measures and divides silk threads according to the desired length and thickness.

- Dyeing – The threads are repeatedly immersed in dye to achieve smooth, even coloration. Creating subtle gradations or shades requires years of experience.

- Reeling and Measuring – Dyed threads are wound onto small spools and measured to uniform lengths.

- Twisting – The threads are twisted to add strength and gloss.

- Braiding – The artisan uses a marudai, kakudai, or takadai stand, crossing threads with steady tension to form precise patterns.

- Finishing – The ends are untwisted into tassels, steamed, and polished to a smooth texture.

Every step demands precision. If even one thread is pulled too tightly or too loosely, the pattern will lose its balance.

Modern Kumihimo — Tradition That Adapts to the Times

Today’s kumihimo artisans continue to preserve traditional skills while exploring new directions.

Ryukobo, based in Tokyo, produces kumihimo accessories using plant-dyed silk threads and offers workshops for visitors.

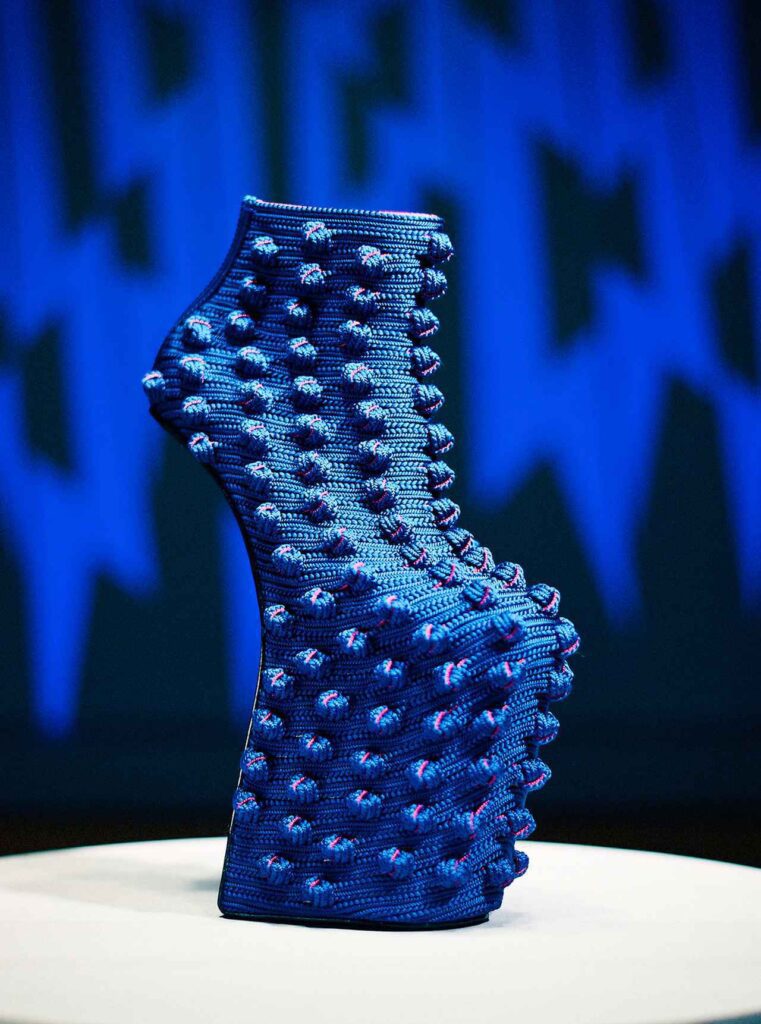

The company also collaborated with contemporary artist Noritaka Tatehana to create the KUMIHIMO Heel-less Shoes, applying the structural strength of braiding to modern design.

Meanwhile, Kyoto kumihimo makers continue to develop new colors and patterns suited for both kimono and Western fashion.

These efforts show how kumihimo remains a living craft—flexible, functional, and deeply rooted in Japanese aesthetics.

Where to Experience Kumihimo

Yūshoku Kumihimo Dōmyō (Tokyo, Kagurazaka)

Founded over 350 years ago, Dōmyō is one of Japan’s most respected kumihimo workshops.

Its English-supported programs allow participants to learn authentic braiding using a marudai stand under professional guidance.

- Address: 6-75 Kagurazaka, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo

- Hours: 10:30 a.m.–6:30 p.m.

- Phone: +81-3-3528-9874 (Shop / Experience)

- Website: https://kdomyo.com/en/pages/museum-english

Ryukobo (Tokyo, Bunkyo Ward)

Ryukobo offers workshops using its original plant-dyed silk threads.

Beginners can try short courses such as the “Mini Marudai Experience” (60 min) or the “Finger Braiding Course” (40 min).

- Address: 2-34-9 Sendagi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo

- Fee: from ¥3,000 (tax excluded)

- Website: https://ryukobo.jp/workshop/

The Culture of Tying — Why Kumihimo Endures

Kumihimo continues to exist because it is still part of everyday life.

It ties obi belts, wraps gifts, and secures sacred ornaments in religious ceremonies.

Each act of tying carries the meaning of connection—between people, generations, and traditions.

Every strand embodies patience, precision, and care, reminding us that beauty can be found in the quiet rhythm of human hands.

What Is Traditional Craftsmanship?

Traditional craftsmanship refers to handmade artworks that have been passed down through generations using time-honored techniques and materials.

Items officially designated as “Traditional Crafts” by Japan’s Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry or by prefectural governors must meet the following criteria:

- They are practical items used in everyday life.

- They are mainly handmade.

- They use traditional materials and techniques.

- They are continuously produced in a specific region and form a local industry.

These conditions ensure that the craft is not only an art form but also a living part of Japan’s cultural heritage.

Editor and writer from Japan. Not the best at English, but I share real stories with heart and honesty — aiming to connect cultures and ideas that matter.