Sashiko ∣ Japan’s Stitch Art of Strength and Prayer

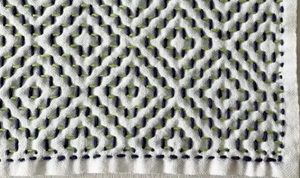

Sashiko is a traditional Japanese handcraft in which geometric patterns are stitched with thread onto fabric for reinforcement, insulation, and decoration. It spread as the wisdom of common people during the Edo period, developing as a technique to repair and reuse clothing while adding beauty to everyday life. Today, its simple warmth and rhythmic patterns are once again in the spotlight, reaching into fields such as fashion and art.

What Is Sashiko? Japan’s Traditional Stitchwork for Strength and Beauty

Sashiko is a traditional Japanese handcraft in which geometric patterns are stitched with thread onto fabric for reinforcement, insulation, and decoration. It spread as the wisdom of common people during the Edo period, developing as a technique to repair and reuse clothing while adding beauty to everyday life. Today, its simple warmth and rhythmic patterns are once again in the spotlight, reaching into fields such as fashion and art.

History of Sashiko ∣ Craftsmanship Rooted in Edo-Era Life

The origin of sashiko is believed to date back to the 16th century. It flourished particularly in the cold regions of northern Japan, where layers of cloth were stitched together for warmth and durability.

Cotton was extremely valuable at the time, and people repeatedly mended their clothes as part of daily wisdom. Sashiko not only strengthened the cloth but also made it more beautiful—an embodiment of Japan’s mottainai spirit, cherishing every piece of fabric.

Its stitched patterns were also believed to offer protection, good harvests, and family health, carrying wishes and prayers into daily life.

Japan’s Three Major Sashiko Styles ∣ Kogin-zashi, Shonai, and Otsuchi

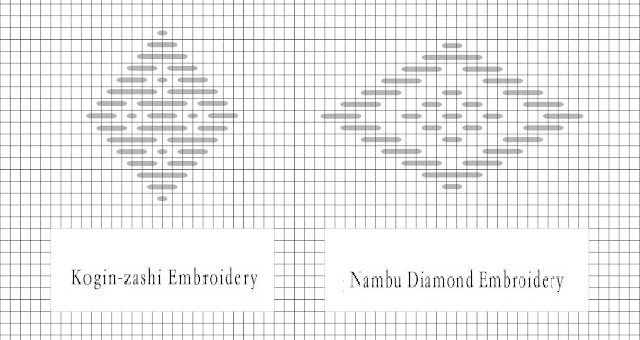

Aomori (Kogin-zashi / Hishi-zashi)

In the Tsugaru region, “Kogin-zashi” developed as white cotton thread was stitched over linen cloth, counting the weave of the fabric. The resulting geometric patterns are beautifully symmetrical. In the southern Nambu area, “Hishi-zashi,” based on diamond shapes, evolved as the embroidery of farmers’ workwear.

Yamagata (Shonai Sashiko)

“Shonai Sashiko,” dating from the early Edo period, was said to have been started by the wives of samurai as they mended family garments. In Yusa Town, artisans still stitch freehand without using outlines—a style called yokosashi—with designs inspired by mountain worship unique to the region.

Iwate (Otsuchi Sashiko)

In Otsuchi, Iwate Prefecture, local women revived sashiko as part of the “Otsuchi Sashiko Project” after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. It has become both a symbol of recovery and a modern expression of traditional craftsmanship.

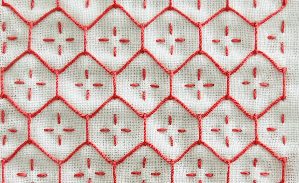

Meanings in Sashiko Patterns ∣ Wishes Woven into Geometry

Sashiko patterns have long carried the hopes and prayers of the people.

- Asanoha (Hemp Leaf): Represents a wish for children’s healthy growth, like hemp growing tall and straight.

- Shippo-tsunagi (Linked Seven Treasures): Symbolizes harmony, prosperity, and lasting connections.

- Kikko (Tortoise Shell): A symbol of longevity and good fortune.

- Kaki-no-Ha (Persimmon Leaf): Expresses wishes for a strong, fruitful life and rich harvests.

- Kagome (Basket Weave): A pattern believed to ward off evil spirits, inspired by bamboo basket weaving.

These geometric designs are not merely decorative—they are visual forms of prayer, stitched into the fabric of everyday life.

Firefighters’ Coats ∣ The “Iki” Spirit in Hidden Beauty

In Edo-period Japan, firefighters wore hikeshi juban—cotton coats reinforced with sashiko stitching. The outer fabric was black-dyed cotton, while the lining often displayed dynamic motifs such as waves and ascending dragons.

The dragon, a creature that controls water, was seen as a symbol to suppress fire. This hidden decoration reflected the iki (refined spirit) of Edo—beauty concealed beneath functionality, where protection and aesthetics coexisted.

Sashiko Today ∣ Revalued as Visible Mending

Although no longer a necessity, the warmth and handmade texture of sashiko continue to fascinate people today.

From dishcloths and coasters to denim repairs and interior accents, sashiko finds new roles in daily life. Overseas, it is admired as “visible mending,” representing a sustainable lifestyle and mindfulness in making.

Sashiko Gals ∣ Women Sharing Sashiko with the World

The “Otsuchi Sashiko Project,” founded in Iwate Prefecture after the 2011 disaster, continues to preserve and share sashiko through women’s craftsmanship.

As part of the fashion brand KUON, they work under the name Sashiko Gals, revitalizing old textiles through sashiko customization. Their work has been featured in The New York Times, HYPEBEAST, HIGHSNOBIETY, and SSENSE, earning global recognition as a sustainable expression of traditional Japanese culture.

Experience Sashiko

At the handcraft shop canoha in Ogikubo, Tokyo, visitors can join beginner-friendly sashiko workshops.

What once emerged as a necessity to preserve fabric is now enjoyed as a slow, meditative craft. In the “sashiko dishcloth” workshop, participants choose fabric and thread colors to create their own patterns, stitch by stitch.

The finished cloth can be used not only as a dish towel but also as a handkerchief, lunch mat, or wrapping cloth.

canoha(Eng)

The Warmth of Hands Beyond Time

Sashiko was born from hardship and the effort to make fabric last longer, yet it has become a refined art of endurance and grace.

Each stitch holds a prayer, binding the past and the present together—the quiet rhythm of hands continuing through generations.

You might also be interested in these articles

■The Bamboo Craft You Never Knew – Quiet Strength Woven into Japanese Life and Luxury

■Japan Denim: Rewriting the Rules of Indigo

What Is Traditional Craftsmanship?

Traditional craftsmanship refers to handmade artworks that have been passed down through generations using time-honored techniques and materials.

Items officially designated as “Traditional Crafts” by Japan’s Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry or by prefectural governors must meet the following criteria:

- They are practical items used in everyday life.

- They are mainly handmade.

- They use traditional materials and techniques.

- They are continuously produced in a specific region and form a local industry.

These conditions ensure that the craft is not only an art form but also a living part of Japan’s cultural heritage.

Editor and writer from Japan. Not the best at English, but I share real stories with heart and honesty — aiming to connect cultures and ideas that matter.